A Review of Rick Swan's The Complete Guide to Roleplaying Games

The First in a Series on Books Every Table Top Gamer Should Own

In November of 1990, the world of role playing games was still largely a mystery to the majority of mass culture. Most people "knew," thanks to the culture wars, that D&D was devil worship and it made you go crazy like Tom Hanks in "that" made for TV movie. There had been some products released in the 1980s that attempted to convey to the lay person what role playing games were about and what some of the best role playing games were. These products did a good job of introducing the concepts, systems, and assumptions underlying role playing games as a hobby. They also provided great information to those who wanted a better understanding of these games than the evening news was providing them. Sadly, not enough people read these books and some of the misconceptions regarding role playing games linger into the modern day.

While the concept of what role playing games are was a mystery to the majority of the public, the vast array of products available and whether they were of good quality or not was largely a mystery to the majority of gamers. Unless you subscribed to The Space Gamer, White Dwarf (before it became all Warhammer all the time), The Dragon, Different Worlds, or some other gaming magazine, you had no source for thoughtful and accurate reviews. Since most of these magazines were relatively obscure to the mass market consumer and often weren't available at your local bookstore (The Dragon being the exception), there was a need for a readily accessible resource for the novice consumer.

Since the creation of the role playing game hobby in 1974 with the publication of D&D literally hundreds of new games, in a wide variety of genre, have been published. Thanks to the internet many of these games are still in print. Publishers like Precis Intermedia are hard at work trying to keep even obscure games in print and available to modern gamers. Even so many games that existed and came into print have faded away and might be forgotten. In the 1990s, things were much worse as there weren’t pdf marketplaces nor independent publishers trying to resurrect older games.

Unless you had a phenomenal hobby store in your local community you were likely unaware of the vast majority of these games. If you did have a great hobby store, it likely had several obscure games that were expensive for the times and didn’t have great word of mouth. How could you know whether or not to spend your hard earned lawn mowing money on these games?

Into this product rich and information scarce environment arrived a perfect catalog for the role playing aficionado, Rick Swan's The Complete Guide to Role-Playing Games. Even if the "complete" in the title was a bit of an exaggeration, there were many games excluded from the book, the volume is was an invaluable resource for the gamer who wanted to know what was available in 1990 and whether it was any good or not. The fact that the book is topical today is a testimony to the insightful reviews provided by Rick Swan. The majority of the reviews are true reviews and not merely product recommendations. This is because the reviews don't merely provide a recommendation pro or con a particular product, they also give a glimpse into the history and mechanics of the game. One can determine whether a particular review is a true review or a mere product recommendation by asking themselves one simple question about the review, "does this review add value to the 'art' in addition to evaluating a particular product or work?" In the case of games, a "true review" would include meaningful discussion regarding game design -- from either a mechanical or narrative perspective. Many of the reviews in Rick Swan's book meet this criterion.

This isn't to say that I agree with every review, I don't, but it is to say that the vast majority of the reviews in this book are a worthy read for gamers of any generation.

An example of an argument that Swan presents in the book that has shaped the way I view my hobby (how often can you say a review has shaped the way you view a particular medium?) is this section of his review of the Dungeons & Dragons Game -- in this case the Red Box Basic Set and not AD&D:

Purists grumble that D&D isn't just simple, but simple-minded. The rigid character classes give players little freedom in customizing their PCs, and advancement by levels is arbitrary and unrealistic. The magic system and combat rules are illogical, Armor Classes represent the chance of being hit rather than offering protection from damage, experience points are meaningless and abstract, the adventures are juvenile... you get the idea.

These grouches completely miss the point. Complaining that Dungeons and Dragons is an unrealistic RPG is like saying that chess is an inaccurate wargame. We aren't talking about delving into the social structure of medieval Europe here, we're talking about tossing fireballs at lizard men and swiping gold pieces from ogres. Dungeons and Dragons provides a streamlined, easily mastered set of rules that emphasizes action and adventure. And as a bonus, it's an excellent introduction to the entire hobby.

This is only a small section of Swan's review of the D&D game, which he gives 3 1/2 stars out of 4, but within these two paragraphs you can begin to see an underlying philosophy of what role playing game design should focus on. In this case, the argument is that it is perfectly appropriate for a game to focus on fun at the expense of realism. It’s an argument that Gary Gygax often made in The Dragon while defending his creation and it’s the argument that John Hill made in his defense of Squad Leader. Amazingly, many of the criticisms launched at Basic D&D can be heard in the criticisms many people used when discussing 4th Edition. They often said that the game was overly simple, for MMORPG obsessed teens, for those too stupid to understand the complex rules of 3.5, and a score of other statements that echo the sentiments that Swan critiques in his defense of Basic D&D. Like the Basic Set, 4e was an excellent introduction to the entire hobby. We should remember, as I saw someone remind everyone the other day on the Book of Faces, that like Basic D&D the 4th Edition was many people’s introduction to the hobby.

As I mentioned above, Swan's review of D&D is one of the things that helped shape my appreciation for the gaming hobby and helped me form my underlying philosophy. My philosophy is simple, the system should serve the intention. It’s my own adaptation of the aesthetic argument that form follows function. Contrary to how it’s often applied in architecture, in the case of my gaming philosophy, ornament isn't necessarily excess as I believe that in games ornament can be the purpose. Take for example the case of narrative "fluff" which could be described as ornamentation surrounding the mechanical design of the game and thus excess, yet for me the fluff is many times the best part of a game. The telos/ends of gaming is "fun." Though that word can have many definitions, it is the goal of the game designer (and the DM and players in interactive role playing games) to play toward the goal of fun. Needless to say, fun trumps verisimilitude at every turn in my gaming philosophy. I'm not a purist. I like elements of chance introduced into my games. Then again, much to the dismay of Adolf Loos, I adore art nouveau.

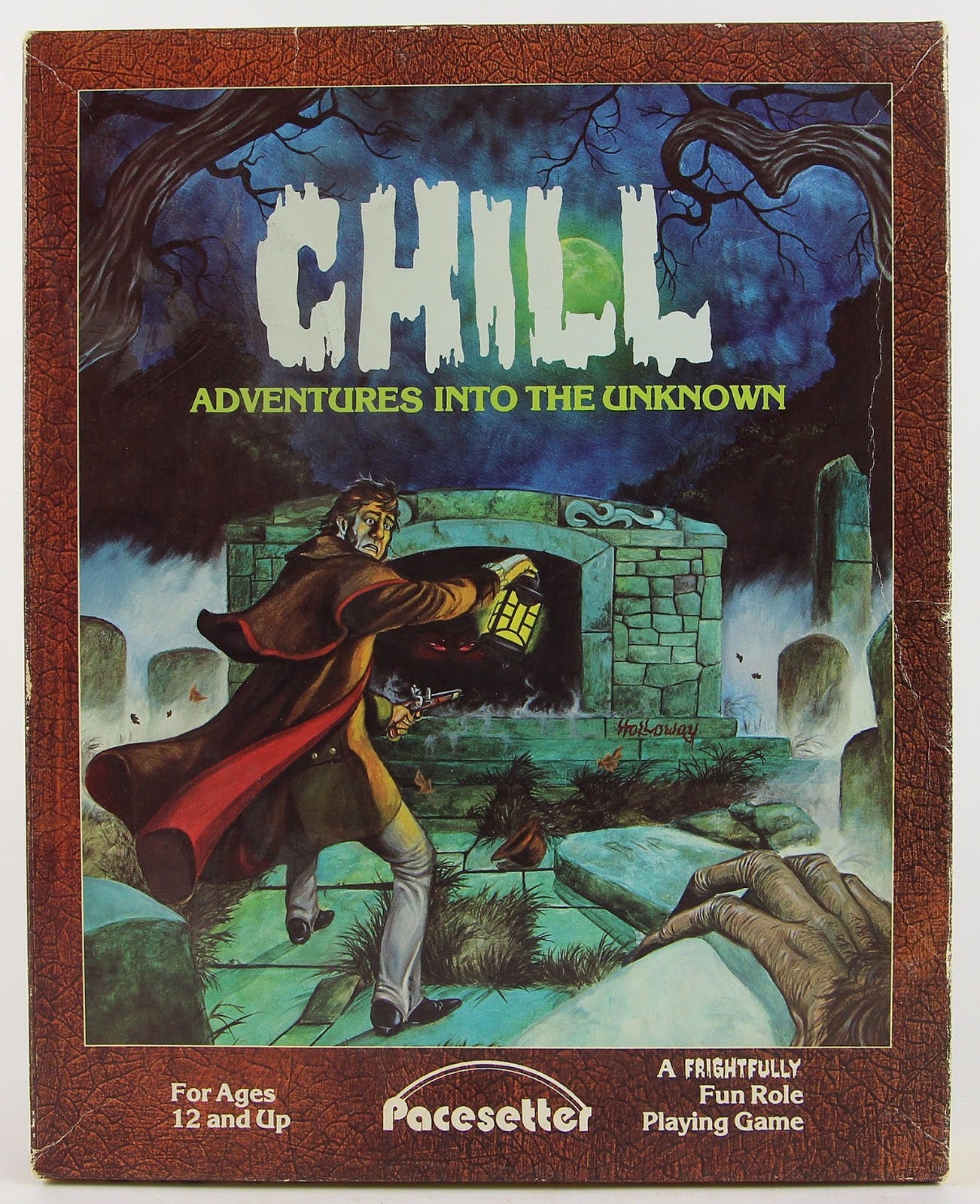

It is this love of "form follows fun," that also points to the review where I most disagree with Mr. Swan. He is unkind to the classic Pacesetter game Chill. A game that is sadly out of print, but is available in a legacy sequel version called CryptWorld (a perfect Halloween gift to yourself). According to Swan Chill is:

a horror game for the easily frightened...While most of Chill's vampires, werewolves, and other B-movie refugees wouldn't scare a ten-year-old, they're appropriate to the modest ambitions of the game...Though it's been out of print for years, Chill remains as popular as ever on the convention circuit. I'm not sure why...Chill is too shallow for extended campaigns and lacks the depth to please anyone but the most undemanding of players.

I guess for Mr. Swan it's okay for a fantasy game to be about throwing fireballs at lizard men, but it isn't okay for a horror game to be based on the Universal Classic Horrors or the glorious Hammer films. Mr. Swan, it seems, is only satisfied by the deeply nihilistic cosmic horror of the Lovecraftian kind exemplified by Call of Cthulhu where life is meaningless. Too bad, Chill has some wonderful fodder for the Game Master well versed in the classic horror tale who wants his players to be ghost hunters like the Winchester Brothers rather than gibbering lunatics who have seen what man was not meant to know. I have always been struck by how an individual can defend the simple gateway game on one hand, but then dismiss another because it isn't high art. And that criticism can apply to any number of critics.

Disagreements like the assessment of Chill aside, the book is a wonderful and necessary edition to any gamer's library and Rick Swan is an able and careful reviewer.

![[] []](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F174efeb3-45c1-4937-bbaf-3ce965ed34ac_1053x1600.jpeg)

![Dungeons & Dragons Basic Rules, Set 1 [BOX SET] Dungeons & Dragons Basic Rules, Set 1 [BOX SET]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd215eef6-7548-4758-9b46-49730ad9905a_800x1000.jpeg)