Gaming Expectations: Heroic Endings or Doomed to Failure (Case Study One: Robotron 2084)

Responding to Things We Think About Games

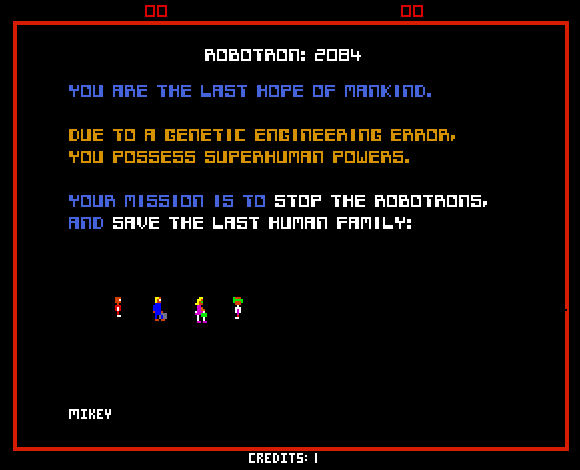

“The player is tasked with the grim, desperate, and ultimately futile task of saving the last family of Humanoids.”

Bill Loguidice discussing Robotron 2084

In 2008, game designers Will Hindmarch and Jeff Tidball released a very useful book entitled Things we Think About Games. The book contains 101 statements by the authors, with a couple of additional statements by guest gamers/designers. Some of the comments are common sense, some are blunt, and all are thought provoking. Things We Think About Games is a book that belongs on every gamer's bookshelf, and Will and Jeff's website belongs on every gamer’s regular rotation of reads.

Many moons ago at a San Diego Comic Con lost to the mists of time, I asked Jeff Tidball if he would allow me to write a series of posts discussing the various statements from the book. Each blog post would be a gamer reacting to one of the statements in the book, and eventually I'd like to address all the statements made by the various game designers. One could think of it as “Things I Think About Things We Think About Game,” or in more intuitive terminology as a series of responses to their book.

This being a blog, and not a Thesis or Dissertation, I will address the statements in no particular order, but I do hope to address them all and maybe someday pitch Will and Jeff a book version of my responses to their statements. Since I’m not constraining myself to any logical order, today's postg is inspired by the 101st entry in the book.

STATEMENT 101

Know Why You Play Games.

The statement is simple enough, and is in many ways a gamer's version of Oracle of Delphi's famous dictum gnōthi sauton (νῶθι σαυτόν) or "Know Thyself." Knowing why your players play games, is a vital foundation for being a good Game Master. It is also a statement seems to have an underlying claim that some ludophile version of Socrates might adhere to, and I can imagine this sage saying "the unexamined gaming experience isn't worth playing." That may, in one way, be the whole point of Hindmarch's and Tidball's book, but this quote provides a nice starting point for any discussion regarding games and spurs one on to think philosophically about the subject.

It was this thought that was lurking around my subconscious when I read an article at GameDeveloper about Robotron 2084. I’ve been reading a lot of articles and watching a lot of videos regarding retrogaming of late and Robotron is one of my absolute favorite games. This particular article is an historical article about the game and its legacy with regard to game play. A good amount of time is spent discussing the games innovative use of a two joystick system, an innovation that couldn't be accurately emulated in a "home experience" for many years. It makes for interesting reading, but there was one quote which mixed with Statement 101 that prompted me to think about why I play games. The quote was a simple one, "The player is tasked with the grim, desperate, and ultimately futile task of saving the last family of Humanoids (emphasis added)."

Ultimately futile -- the words echoed in the back of my mind.

Why would I want to play a game that I cannot, no matter how skilled I get at it, "win?"

What particularly bothered me about this statement is that it pointed to a contradiction in my game playing habits. I have been a fan of Robotron 2084 for decades and have played it uncountable times. In that time my skill level has migrated, from poor to excellent to poor to average, depending on how often I have played the game during a given time period. I am not always in the mood for Robotron, but I never find the game -- as it was designed -- to be a bad game. As big a fan as I am of this particular futile effort, I was seriously disappointed by the end of Dawn Of War. After many hours of game play, and total victory over the forces of Chaos, I watched as all my hard work evaporated in a "1970s Satan has eaten your soul Bad ending" as my Space Marine Captain unwittingly released a new demon into the universe.

The futility of all my hard work playing Dawn of War was made clear to me during the final animated narrative sequence. Lucien Soulban's scripted ending undid everything I had struggled for in playing the game -- and it seriously aggravated me. I was all the more aggravated because an author/game designer I respect was the one who dropped the "futility bomb" on my head. The ironic thing is, I play Dawn of War at least once a year and every year re-experience this frustration. I love the game. I love the story. I hate the futility of the ending. Yet I return each year.

Why do I experience such a strong emotion that is, on its face, a contradictory sentiment? Why do I experience it more strongly with Dawn of War than I do when I play the equally futile Robotron 2084? To answer this, it was helpful to contemplate Statement 101.

Why do I play games?

I play different games for a variety of reasons, but one reason that keeps me coming back is "story." I like the way that games, of all kinds, tell stories. It's one of the reasons I am a "good loser." I don't mind losing to someone who is better than me at Chess, all I want is my learning experience to be a good story. Candyland, with its pre-determined gameplay, taught me the importance of story in play and de-emphasized "winning." Both Robotron 2084 and Dawn of War contain story elements. Robotron's appear to be "weak" at first, but they are deeply embedded in gameplay -- if simple narratively. Both games contain narratives where the actions of the player, in the end, result in failure. There must be some element of the game and how it interacts with story that allows me to enjoy one in its entirety while feeling dissatisfied with the ending of the other. What is it about the game play that I find frustrating?

Aha!

It isn't the futile ending that is disappointing. It is the fact that the futile ending of Dawn of War is not a part of game play. It was a constructed non-interactive narrative tacked on to the end of the game to remind the player that there are more fights in the future and that “In the grim darkness of the future, there is only war!”

When the player inevitably loses in Robotron it is because the game has finally become too hard to finish, the game has literally beaten you. When you "lose" at the end of Dawn of War, it occurs after you have achieved "final victory." The contradiction lies in the interaction between the mechanics and the story, a contradiction made even stronger by the underlying expectations of Real Time Strategy games. The underlying expectation of an RTS is that you can win, any advantage in supply or troops the computer opponent has is usually made up by an imperfect AI. The AI is necessarily imperfect as a perfect AI would likely win all the time and lessen the fun, but that is a thought for a future essay.

Would I have felt differently if I had actually lost the final scenario of Dawn of War rather than have a scripted 70s ending? Not if the game had followed standard RTS genre conventions, the player "must" have a chance to win in the conventional real time strategy game. What if the game progressed in a manner that seemed to mirror traditional RTS games, where each level gets slightly more difficult but remains winnable, but added a final impossible level? Then the game would have been extremely unsatisfactory to me. My dissatisfaction would only have been magnified by the interstitial narrative clips hinting at my potential to succeed.

On the other hand, if the game lacked interstitial clips and instead had all narrative created as an outcome of game play I might accept an unwinnable level. At least possibly, especially if I knew going in that the game eventually becomes unwinnable as each level becomes more difficult than the last. But that isn't the central conceit of an RTS campaign, the central conceit of an RTS campaign is that the player is unlocking a heroic narrative. In this case, each victory leads to a new chapter in the hero's tale. A hero can hit a low point, like the one at the end of Dawn of War, but that ought not be the end of the story. In this case, it is.

This is because there is no direct sequel to the narrative. Even though there are many sequels to the game, my Blood Angels forever stand defeated in their victory, where my cursed defender of humanity just ends up dead after finally facing overwhelming odds.

I think it would be interesting for someone to design an RTS where each level becomes more difficult than the last, with no end in sight. In such a design the story changes from how my victory was taken from me, to how far I was able to get and who is able to get to the farthest level. Given why I personally play games, I believe I would prefer traditional RTS games with victorious endings to that "futile" RTS. Given my love of Robotron 2084 there is a chance that I'd like that killer RTS more than the end of Dawn of War because the ending would be driven by the mechanics of the game and not a cutscene over which I have no control. I have a similar emotional reaction to Darkest Dungeon, but that will have to wait for a future post.

I don't mind losing when it's a part of the rules, but I hate losing when I won fair and square.

The kids today will never know what it was like when every game killed you eventually unless you somehow managed to crash the computer and get a kill screen, something only the Billy Mitchells of the world ever achieved.

Maybe it was a better life lesson -- some folks score higher than others, but we all die. Instead we now talk about "winning" at life, when it's really all relative.

Get the humanoid. Get the intruder.