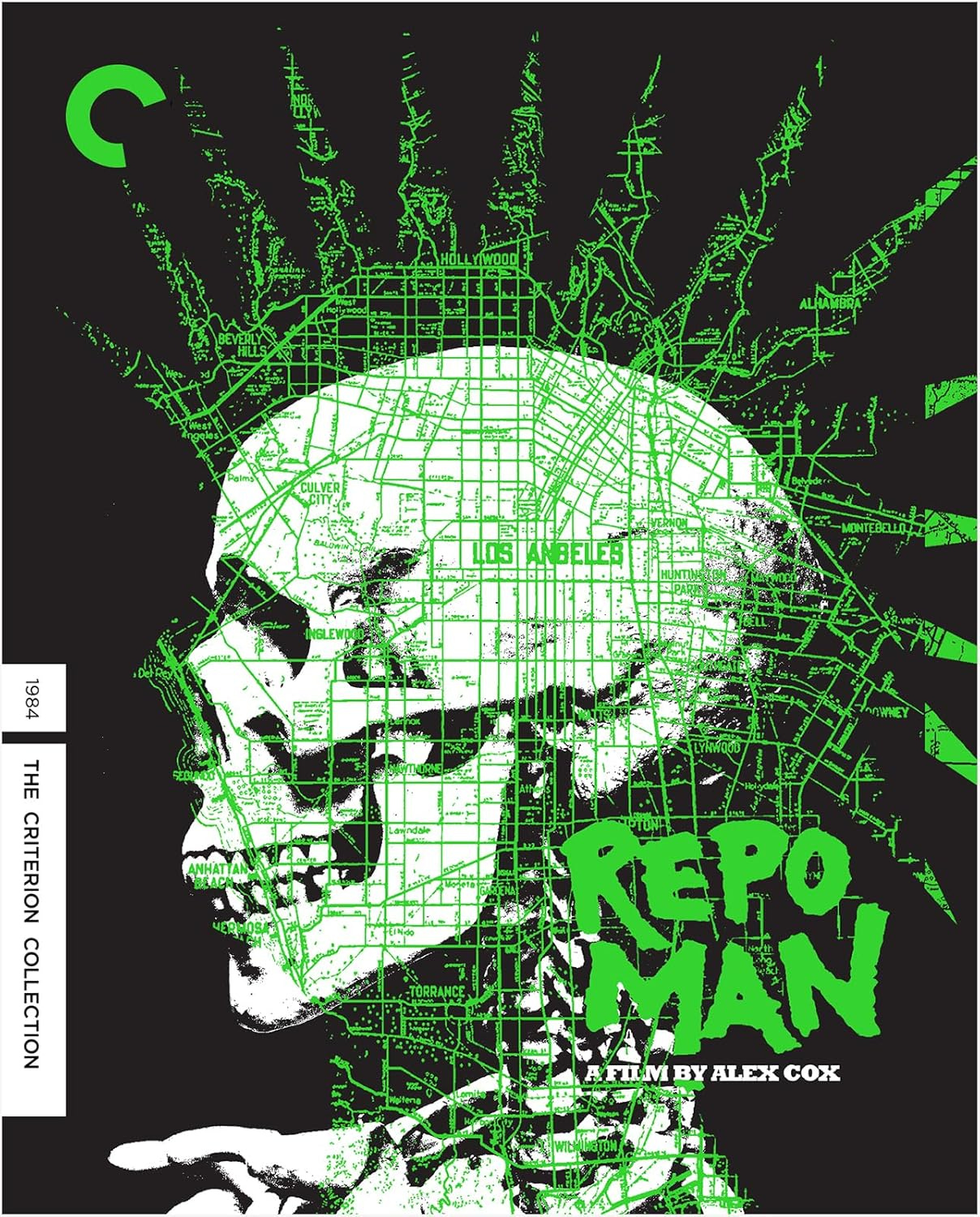

For me, the most memorable thing about Repo Man, which just got a 4K upgrade from Criterion, has nothing to do with the actual film itself, but the circumstances under which I saw it. It was during one of many summer trips to the U.S., which would usually conclude with me and my father spending a few days in New York City, in the apartment of his best friend, an antiques dealer for Sotheby's who lived near Madison Avenue in an ancient, probably rent-controlled, fifth-floor apartment (no elevator) that was about 50% luxury and 50% in a near constant state of visual decay.

My dad would go to all the museums, usually with me in tow, and we'd also try to see about 2-3 movies a day, mostly of the sort that he knew would be age-restricted in Ireland (which was 90% of movies, though they'd show them uncut on TV eventually) but that might have elements that would appeal to me while still expanding my world of cinema. Repo Man, he knew, had aliens in it, which would be enough of a hook.

We went to a late night show, far across town, and afterward, the streets were empty. No cabs, nothing. Well, except for one empty bus with a driver looking casual. My dad called out to him to ask if he was running. The driver made a generic gesture that seemed to suggest we should follow him around the corner. He started up the bus, and drove it out of our sight; my dad commanded me to follow the bus, so I took off running. He followed, slightly more skeptically.

When we got around the corner, the bus was there, with the door open. We got in, and my father asked, “Did you wait for us?” The driver nodded yes, and asked where we were going, so we told him our stop, then went and sat in the back of the bus.

As the bus took off across town, we noticed it never stopped to pick anyone else up. It was night, and it was a dead side of town, so perhaps that was no surprise. However, as we got into more populated areas, people were hailing the bus...and it wasn't stopping. “Luke,” my father said, “I think we're going to fly off into the sky here. It's an alien bus.”

Actually, I'm not sure he did say all that, but in all the years that followed, when he'd tell the story, he would say he did. The bus didn't fly off, of course...but he drove us right to our doorstep. A good Samaritan who had seen a very lost young father and child, and did his kindness for the night.

There's a lot more to remember about Repo Man than that, of course. Even when we saw it, the summer it opened, it had already become a cult movie, with evident fans who would call out certain things onscreen we'd never have noticed. (Look for the “Plate o' shrimp” special.) I had not yet been to Los Angeles, and when my dad laughed at the band name “Circle Jerks,” having zero idea of their musical significance but loving the name, I laughed too, just because it was a funny-sounding moniker – I'm sure he was relieved I didn't ask about any deeper meaning, though knowing him, he would have told me had I done so. Their scene is a meta-joke if you recognize them: punk pioneers dressed up as a lousy house band in cheap tuxes. We were proof, however, that, just seeing a funny-looking band named the Circle Jerks was inherently funny. I had only just discovered MTV – punk rock was not something to compartmentalize yet, though it was through this movie that I first heard the name of Iggy Pop.

(My father, who always claimed his musical tastes were super-eclectic and he liked all types of music, never registered much when it came to punk and heavy metal, probably because he didn't really seem to consider them music.)

Director Alex Cox was a UCLA grad in his early twenties, from England, so he has a bit of an outsider's eye for American weirdness, which I could and can relate to. One of the things that makes the movie so timeless is simpler than it appears – if you focus on the lower classes, your film is less likely to age badly, alas. Gadgets may improve, and phone booths and newspapers aren't omnipresent like they used to be, but the lower classes of the city will still live around warehouses, junkyards, and seedy streets, while drinking beer in empty lots and partying in sparsely furnished homes.

Even the generic blue-typeface food products, which always get a good laugh, were mostly a real thing in LA – I've had them, and that watered-down beer was awful. The Los Angeles of broke folk who can't just go home on the weekends, the city Alex Cox knew in 1984, isn't that different from the city I encountered as a USC freshman in 1992. The downtown skyline is different, but those neon high-rises still feel as metaphorically distant as the background cityscapes in a 16-bit Super Nintendo racing game. Given that on a recent visit to Westwood, I saw pretty much everywhere that I used to hang out shut down, I suspect an out-of-state UCLA student today might find things to be similar.

If you want a really good comparative example of how focusing on lower classes keeps things sadly contemporary, watch the dueling '80s TV nuclear war epics, The Day After and Threads. The former, a U.S. production, focuses on regular folks affected by the situation, most notably a doctor and a farmer. They're well-off by our standards, and their fashion sense is well off of what we'd wear today. The story still has a grim power, but its datedness, and reasonably good-looking stars, even in the face of apocalypse, allow the modern viewer some ironic distance. Threads, from the UK, went for a kitchen-sink realism style, focusing on the working class of Sheffield, and while the TV and video games may look old-fashioned, their homes look the same as many UK urban homes now, and the basic, realistic costume style has the primary characters look like unmade-up humans in functional clothes, at home in any modern era because they're not trying to glam up to the trends. It remains convincingly terrifying.

(Threads is also far more grimly realistic about the effects of radiation and mass detonations, but everyone who knows anything about those movies is already aware of that fact.)

Though it could be made today and look nearly the same, Repo Man is also very much a product of the '80s in its punk rock soundtrack and style, as well as the then-ubiquitous use of corrupt televangelism as a plot point. (That said, punk rock will always be in some kind of style, as long as there are angry youths with more passion than pure musical ability. See previous point about lower classes being timeless.) Before the Internet, California was seen as a mecca for conspiracy kooks and UFOlogists, as seen in the Weekly World News, a tabloid regularly spoofing (we hoped!) such people. Hefty tributes to Kiss Me Deadly and its nuclear weapon abound in the story's central conflict, about the chase to procure a Chevy Malibu with radioactive aliens in the trunk. Two years before Blue Velvet, Alex Cox also makes use of the sort of bizarre non-sequitur dialogue combined with exaggerated expression that would come to characterize David Lynch's work; something about the nation being ruled by a smiling, vacuous actor with the power to end all life on Earth probably had something to do with it.

And then there's Otto, played by up-and-comer Emilio Estevez. I was too young to care about teen movies in 1984, so I'd never seen him before. The viewer naturally gravitates towards him, and as an adult, one might wonder why. He's a spoiled suburban punk, embracing faux-nihilism with privilege, though he loses his parents' financial support early on. He passively falls into the repo trade, which is quintessentially capitalist – let people buy things on credit they can't afford, then snatch them away when the bill comes due and can't be paid. Otto's not particularly nice to anyone, and a scene where he basically sexually harasses his new girlfriend only holds up still because she tolerates none of his crap.

So why do we like him? Because he's passive. Otto does almost nothing to affect the outcome of the story, but he's our eyes and ears into an unfamiliar (to non-Angelenos, at least) world. We learn the rules when he does. His outward appearance as a clean-cut leading man type is deceptive, but it allows him to pass in any situation. Nobody's going to tell a brick faced white teen he can't come in, but they can make things mighty uncomfortable once he does. (It's a nicely understated joke that his primary coworkers are all named after beers: Bud, Miller, and Lite. Otto's full name, Otto Maddox, is a riff on “automatic.”)

Bud, played by Harry Dean Stanton, is the perfect authority figure/veteran for an upside-down world. He has a strict moral code, yet it never stops him snorting meth or committing violence with a baseball bat. In the real world, you'd never trust this guy; in Repo Man, he's the only one who seems on top of it. Mostly. At least when it comes to practicalities. Where he doesn't go is into the realm of spirituality, represented by Miller (Tracey Walter, probably best known to all my readers as Bob, the Joker's Goon, in Batman 1989). Miller has a special level of conspiratorial, shamanic knowledge that the movie more or less vindicates by the end, in what Cox calls the Lattice of Coincidence. (It's more amusing now than it was then that Repo Man specifically mocks Scientology's major tome Dianetics as trash.)

The world of the film tugs Otto between street crime and legal theft, a reality dominated by lies or a fiction that's truer than he knows. That's how the world often feels for someone only recently an adult, trying to grasp everything about their surroundings and systems. In my fifties, I don't need conspiracy theories to tell me how screwed up the world is – but I recognize economics as its own collective fiction that would collapse if we all just agreed to stop believing in it. We're conditioned not to see that as weird, but by signaling blatant weirdness, Repo Man lets us feel once more what it was like to first sense the grand scam, and the profound ineptitude of those running it.

When I was ten, however, I mostly focused on the aliens, and that ending, written on the fly, which feels like a rip on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (credit to R.H, Greene for that observation). Originally, the script ended with Los Angeles blowing up in a nuclear explosion; producers suggested that something less nihilistic might be needed to assuage the studio. The rewrite was the right move – so many '80s movies end in apocalyptic explosions, but only one ends in a glow-in-the-dark car flying into the skies above downtown L.A. Without that ending, the movie wouldn't have stuck with ten year-old me as long as it did, encouraging me to revisit it over the years and find so much more “there” there.

Criterion's Blu-ray already looked good; the 4K transfer feels a little less artificially desaturated, but subtly so – there's not necessarily any need to run out and replace their older Blu if you already own it.

Extras on the Criterion 4K set are all archival, though the commentary track is, as usual for them, accessible on the 4K disc as well as the Blu. Said commentary features Alex Cox, producer Mike Nesmith (yes, THAT one), casting director Victoria Thomas, and actors Zander Schloss, Sy Richardson, and Del Zamora. Unlike on some other Criterions, they're all in the same studio at once, laughing at their own jokes and pointing out Easter eggs throughout as well as discussing alternate casting choices and plot directions that didn't happen. Schloss, a PA on the film who became an actor in it, and later a member of the Circle Jerks, plays the nerdy Kevin, a character whom Cox insists inspired Napoleon Dynamite, but I'm not certain Mormon kids like the Hesses would have been allowed to watch Repo Man. Though it sometimes just descends into everyone laughing at once, it's a good commentary with the right balance of trivia, tech, and fun.

Featurettes mostly include interviews for the 2012 Blu: Iggy Pop gets one all to himself, as he opines that the movie's about a kid who can't get laid until he embraces capitalism, and talks about recording the theme song. Harry Dean Stanton goes way off script in his, as he elaborates on his personal philosophy of predestination and Buddhist self-annihilation. (It made me wish I'd interviewed him sober – the one time we met for an interview, he was very nice, very drunk, and couldn't remember anything.) The rest involve groups or montages with Cox, producers and actors.

For deleted scenes, Cox does something a bit different – he films himself watching the scenes along with Nesmith and neutron bomb inventor Sam Cohen (yes, really!). The most notable of the cut scenes is a more explicit version of the opening sex scene that Otto walks in on, featuring full female nudity and the kind of male-on-female oral that would have landed it an X-rating in the '80s. Other scenes that mainly extend some of the moments are both here and in the TV edit of Repo Man, also included, which features creative PG-swears and all the drug scenes excised, making it so short that Cox had to use previously deleted scenes to extend the run-time. It's fun to include TV cuts, but you have to have more time on your hands than I to actually watch them in full.

Finally, the thick, thick booklet includes a critical essay by Sam McPheeters; the pitch for the movie by Alex Cox, which includes comic strips, budget proposals, and a full synopsis; and a conversation between Cox and the repo man he actually rode with to do research. It's a good amount of stuff for a movie this old and low-budget; perhaps the only other thing one could ask for is a copy of the soundtrack, but I suspect Mondo or someone like that is on the case already.

Repo Man hit me at a formative time in my life, and I'm not sure how it will affect new viewers – my younger wife's biggest takeaway was, “It's good but it goes batshit at the end.” If anything, perhaps its distance from the '80s now makes it as strange as it was to a ten year-old not fully understanding them at the time. But it remains a crucial L.A. movie; one that uses touches of unreality to somehow get more real, and feel like the actual place does, especially when you're young, broke, drunk, and punk as f***. If you've ever lived or loved in this city, it might make for your perfect flashback.

Or flash-forward, if you're ten and live in Ireland.

Repo Man is now out on 4K as part of the Criterion Collection.

I have had this post open in a browser tab for the past 2 months so I could come back and make a comment. Repo Man is my favorite movie. I saw it at the theater when it came out and immediately bought the vinyl soundtrack, I've seen it over the years at midnight movie showings and retro film festivals, I have the special edition CA license plate DVD/sound track package, and there was a point in my life I could pretty much recite the whole script. I wanted to describe why I love it, but I'm not nearly as thoughtful, educated, and insightful about movies as LYT. So, I apologize for the lack of an intelligent comment. In my defense, I drive a lot.

It seems that you are originally from Ireland? I didn’t know that.