D&D Rangers Through the Ages (Part 3): AD&D 1st Edition

From Strategic Review to Players Handbook

Background

When I first launched this newsletter a couple of my first articles dealt with the early history of the Ranger class in Dungeons & Dragons and adjacent games. The first article began with a discussion of the potential inspirations behind the class and ended with an examination of the rules of the class for Original (that’s 3 Little Brown Book) Dungeons & Dragons. The second article expanded on the discussion of potential inspirations and then examined rules for the Ranger and Forrester classes written by David Hargrave in his Arduin Grimoire series.

My desire to discuss the Ranger archetype and its development over the years began with a post by Cam Bank back in 2019 discussing his disappointment with how they were mechanically represented in 5th Edition D&D.

As you can see, Cam thinks that Rangers should be guerilla fighters who use a combination of stealth and skill to defeat their foes. It’s a Ranger concept that I also subscribe to. The term Ranger has been used as far back as 1327 to refer to a forester working for community and/or crown, but that meaning has expanded over time to focus on an application of the skill set to military activities. This shift to military focus is particularly true in America where the term has been used since the 17th century and the current US Army has a Regiment that applies Ranger skills in the field as well as a School that trains soldiers in various Ranger skills and tactics.

The concept of Rangers as a highly skilled combatant, as well as skilled tracker, can be seen in Edmund Spenser’s Shepheardes Calender (sic) of 1579.

An examination of this satirical poem, which is highly metaphorical, reveals the context of the quote regarding Wolves. We aren’t talking just about the animal here. The two shepherds of the poem are also talking about foreign invaders.

Oh, and where else are you going to see references to Edmund Spenser in analysis of D&D classes? You really should see more discussion of Spenser in D&D discourse since his poem The Faerie Queene is one of the major influences on Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp’s excellent Compleat Enchanter stories that are a cornerstone of Gygax’s Appendix N.

There’s a lot to unpack in the Shepheardes Calender, and this is not really the place to do it, the point here is that the term Ranger was already being used in England in a manner suggestive of the stealthy combatant Cam Banks and I believe the class should embody.

An equally old definition of the Ranger has interesting implications for the class, while also demonstrating that the term has meant more than game warden for quite some time. This definition may be why the term Ranger is used as an almost slur when describing Aragorn in Fellowship of the Ring.

And while the good Professor Tolkien may have also been taking advantage of the fact that Ranger had for a time also meant “rake” and thus had a less than flattering undertone, he was primarily taking advantage of the archetype of stalking huntsman evoked by earlier lore and military application.

From Soldier to Animal Handler

One of the things that Cam didn’t like about the newer 5th edition Ranger was the focus on having a pet companion. Interesting in his commentary was that he included Tarzan in his list of archetypal Rangers and argues that he didn’t have any animal companions. I mentioned in the last post on this topic that Tarzan did have Jad-bal-ja the lion, but that his association with Tarzan was more like the companions a high level ranger acquired in the original design by Joe Fischer. Jad-bal-ja was an ally, to be sure, but he also had more agency than the animal companions of later editions of D&D. He certainly has more agency that Drizzt’s companion Guenhwyvar had early on in the stories. Guenhwyvar was, after all, summoned by a Figurine of Wonderous Power and not due to any innate Ranger ability.

As a part of the discussion, game designer TS Luikart (The One Ring, Dragon Age, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay) pointed out that a couple of characters who might be classified as Rangers did in fact have animal companions.

I think it is interesting to classify Dar and John Carter as potential iconics for the Ranger class. I don’t think that early gamers thought of Dar as a Ranger type character, or we wouldn’t have seen various adaptations of the Beastmaster as its own class in the early D&D community and we saw quite a few of those. An examination of those will have to wait for my later examination of the evolution of the Barbarian class. While the early D&D community might have wanted an entirely new class for it, I do think that things like “Preferred Enemy” and other evolutions of the Ranger Class in later editions of the game show that in the long term he’s a Ranger.

What about John Carter? Sure, he’s the “Greatest Fighting Man on Three Worlds,” but does he exhibit any Ranger characteristics. I’d say that his experience as a combatant in the U.S. Civil War, as well as his interactions with various beasts of Barsoom, suggests that it might be a good fit for the kind of fighting man he is. Carter is very much the guerilla fighter in the Martian novels and there’s Woola.

Speaking of Woola, when exactly did Rangers become full fledged animal handlers? Sure, in Joe Fisher’s original version of the class it was possible for them to acquire a Werebear companion, but it was also possible for them to have a Gold Dragon or Stone Giant companion. We don’t see a lot of modern Rangers walking into town with their Stone Giant buddy, though Cam’s Jack the Giant Slayer might. Then again, a lot of new players don’t have to fight 4 Balrogs in their first D&D session either.

Though Joe Fisher Rangers had extraordinary followers, they never acquired actual pets. The closest they got were mystical creatures like Pegasi, Unicorns, or Werebears. This may make the Swanmay of The Compleat Enchanter a Ranger (and you thought the Spenser and de Camp references were done), but it doesn’t make a Ranger a character that typically hangs around with animals as companions.

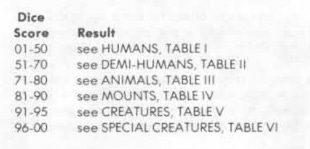

That changed with the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Player’s Handbook. While the PHB made rangers have to wait until 10th level, instead of 9th, to acquire their Merry Band of Followers, the nature of the kinds of followers changed between the Strategic review article and the publication of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. The PHB stated that Rangers acquired 2-24 followers at 10th level that were determined by the Dungeon Master, but the PHB leaves out how the type of follower is determined. That mystery is answered in the Dungeon Masters Guide and it is a significant change from the Strategic Review version of the class.

In the revised version of the Ranger that Gygax presented in the Players Handbook (there is no apostrophe in the original), the Ranger is more than a lone wanderer who has a couple of unique allies. He is a lone wanderer who probably has pets. There are two things that contributed mechanically to this change. The first is the update to the list of followers the Ranger acquired at higher levels. In the Strategic Review version of the Ranger, the chance of of an individual follower being a special companion was only 1%, far lower than the 9% chance that the individual follower was 3 Hobbits. There are no modifiers to this roll, you just roll once on the table below for each of your 2-24 followers.

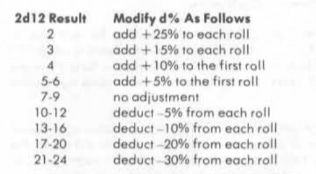

This changes significantly in the Dungeon Masters Guide (once again, no apostrophe in the original). On page 16, the Dungeon Master is advised to modify the rolls on the follower type charts based on the number of followers acquired.

These modifications make it much more likely that a Ranger with a lot of followers has a lot of Human followers. A player who rolls a lot of followers is more likely to have companions that look more like Robin Hood’s Merry Men than Dar’s beasts.

As you can see from the combination of the two charts, you are much more likely to get a Dar like character if you roll low on your initial companions. Your chance of having Human followers (if you roll 3) is reduced by 15% and your chance of acquiring a Special Creature increases by the same amount. The rules are very clear, both in the paragraph before the tables and on the generation tables, that a Ranger can only roll once on each of the extraordinary tables which eliminates the ability to have a Storm Giant and Copper Dragon follower. This is good because a Storm Giant is far more powerful than the Stone Giant (or Hill Giant) the Strategic Review Ranger was limited to having.

Another difference from the Strategic Review Ranger is that the Players Handbook Ranger has a 20% chance for his follower to be a “pet.” I’m very intentionally limiting pets to the Animal and Mounts tables, but there are a couple of pets on the other tables as well. Regardless, a 1/5 chance (broadly speaking) to have one of your rolls result in a pet means that the Ranger is very likely to be an animal handling character. But that isn’t the only change that shifts Ranger from Jack the Giant Killer to Tarzan.

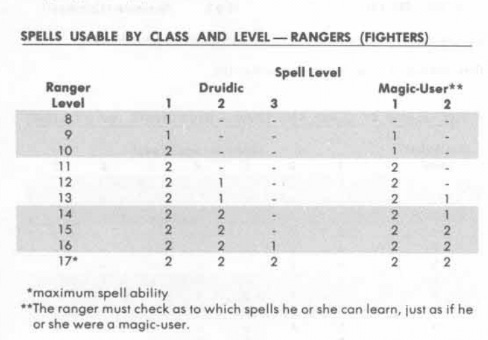

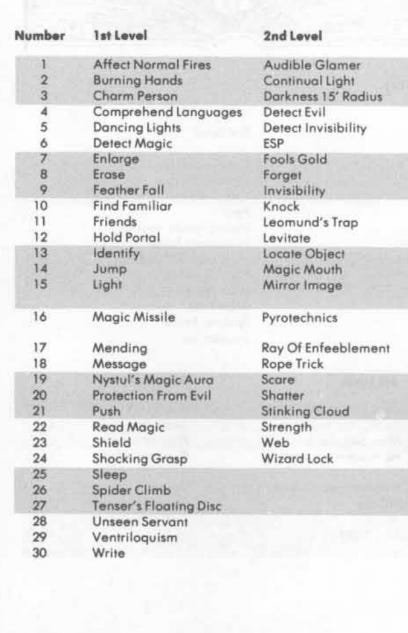

The biggest change is in the spell list that the Ranger gets access to at higher levels in the Players Handbook version. The Strategic Review Ranger has access to Cleric and Magic-User spells of the First through the Third level. If you examine that spell list, you’ll see a lot of spells that might thematically fit with the lone wandering guerilla fighter. No, I’m not talking about Fireball and Lightning Bolt, those don’t fit that archetype, but Hold Portal, Detect Invisible, Infravision, Speak with Animals, and Remove Curse do. One can imagine Aragorn using these, and maybe even pick out scenes where he does so using nature based rather than scholarly magic to do so. How verbal, somatic, and material components manifest in a game are a mere matter of special effects. So having Aragorn’s attempts to cure Frodo after he had been pierced by the Morgul-knife is perfectly emulated by Fisher’s Ranger in Strategic Review.

The Players Handbook Ranger has a very different spell list and the first change that pops out to me is that 3rd Level Magic-User spells are no longer on the table. All those Fireball throwing Rangers have gone the way of the Dinosaur, but it’s the shift from Cleric to Druid spells that really changes the options available. Look at all those “animal” spells.

You’ve got Animal Friendship (which is magic), Invisibility to Animals, Locate Animals, Speak with Animals, Charm Mammal, and Hold Animal. This list shifts the class far more into “deals with animals” mode and given the combination of spells I’d say that it becomes even more “Aragorny” and “Tarzanish.” Yes, we’ve got more spells in general, but we also have more spells that simulate abilities that these kinds of characters might have in their tales. We do have one spell that stands out as mildly inappropriate in Call Lightning, though anyone who has seen the final Michael Praed episode of Robin of Sherwood might not think it’s completely outside possibility.

The Magic-User list contains a large number of “utility spells” that round out the Ranger’s woodland skills and would make it a significantly better Guerilla fighter. As I’ve mentioned in the past, I believe that one should take a special effects approach to D&D magic and realize that instead of needing to constantly invent new spells and abilities one can ask how to change the “special effect” of a spell achieve the desired outcome. Instead of saying “My Ranger casts Magic Missile at the Orc King,” it might be better to say “My Ranger uses his bow to fire five unerring arrows at the Orc King.” The effect would be the same, five magic missiles being cast by an 9th level character. The AD&D rules don’t have a “caster level” concept and spells are based on “experience level.” An 9th level Ranger may only have access to one first level spell, but that spell is (arguably) cast at the 9th level of experience since there is no contrary information. I’d argue that this is the best way to interpret the rule because of the typical foes a name level character would face.

Some might argue that my effects based way of looking at spells breaks the Vancian tone of the magic system. In some ways it does, but in others it doesn’t. In the case of Magic Missile, the spell requires both Verbal and Somatic components. If I imagine that firing the five Unerring Arrows of Herne the Hunter requires a complex prayer and the use of the bow, then I’ve met the requirements of the system while changing the visual. Not once have I changed the mechanics, just the “skin” on them.

Two Weapon Wielders?

The Ranger was expanded to become more “pet” and nature oriented in AD&D. It’s a move that simultaneously made the class more and less like Aragorn, but when did it become common for Rangers to wield two weapons? As you might guess my prior articles on the Ranger, it likely wasn’t Drizzt who signaled this change.

I’d argue that Drizzt marked that this change had become foundational to the class, but that is a topic for my next essay in this series. While you are waiting for that, and the one I’ll be doing on The Barbarian, check out the prior two entries in the D&D Rangers series.

Super article! Great depth and history. I always learn something new that deepens my love for OD&D.

I read Edmund Spenser in university and absolutely loved it. Easy to see how it influenced D&D - thanks for bringing that up!