Some Background

I recently uploaded an old podcast episode where I and the other Geeks and Geekerati interviewed Erik Mona about Paizo Inc.’s now defunct Planet Stories line of fiction. Listening to this interview again reminded me of how much I love Pulp Fiction and Planetary Romance in particular. Catherine Lucille Moore is one of the major Pulp Era authors of Weird Fiction and Planetary Romance and I thought it would be a good time to revisit some of her fiction.

Episode 49: Erik Mona discusses Planet Stories

I’ve long been of the opinion that one of the differences between Planetary Romance and Sword and Sorcery Fiction is that Planetary Romance is filled with tales of daring do with a dash of Edwardian morality, where Sword and Sorcery fiction contains some element of Weird Horror. I’ll share a post on this later this week, but I mention this because C.L. Moore’s tales are a fairly major exception to the rule especially when it comes to her Northwest Smith tales.

Where do these tales fall?

Are they Weird Fiction or are they Planetary Romance?

I don’t consider them Sword and Sorcery, for while they contain sorcery they are tales of Science Fantasy much closer to the Planetary Romance of Edgar Rice Burroughs than Robert E. Howard’s tales of Conan and Kull. They do, however, share more tonally with Howard than much of Burroughs. Which brings me back to my original question.

Where do these tales fall? (Yes, I’m looking for your thoughts here.)

I’ll be starting my exploration of C.L. Moore’s fiction with her Northwest Smith tales, but as time passes I’ll read her Jirel of Joiry tales and more. For this initial pass, I will be using Paizo Publishing's excellent and sadly out of print Planet Stories edition of Northwest of Earth, which contains the complete stories of Northwest Smith (including "Nymph of Darkness" a collaboration with Forrest J Ackerman and "Quest for the Starstone" a collaboration with Henry Kuttner), as my reference during the discussion.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with Northwest Smith, he is often discussed as the fictional character who is the inspiration for George Lucas' character Han Solo. Any need to point out similarities between Northwest Smith and Indiana Jones seems unnecessary, as the names themselves speak volumes about that connection. According to John Clute's Encyclopedia of Fantasy:

"Through Smith, CLM helped revamp the formulae of both space opera and heroic fantasy. Smith's introspection and fallibility give him a more human dimension than his predecessors in heroic fantasy, and the depiction of his sexual vulnerability represented a psychological maturity uncommon in the field."

I think it bears mentioning that Stephan Dziemianowicz, who wrote the entry in the Encyclopedia, makes no mention of Planetary Romance in the Northwest Smith section and focuses on Smith's importance in space opera and heroic fantasy. I do consider Planetary Romance a sub-genre of heroic fantasy, but then again so is a great deal of fiction that no one would ever imagine being classified as Planetary Romance such as Howard’s tales of Sword and Sorcery.

Where does Shambleau fit?

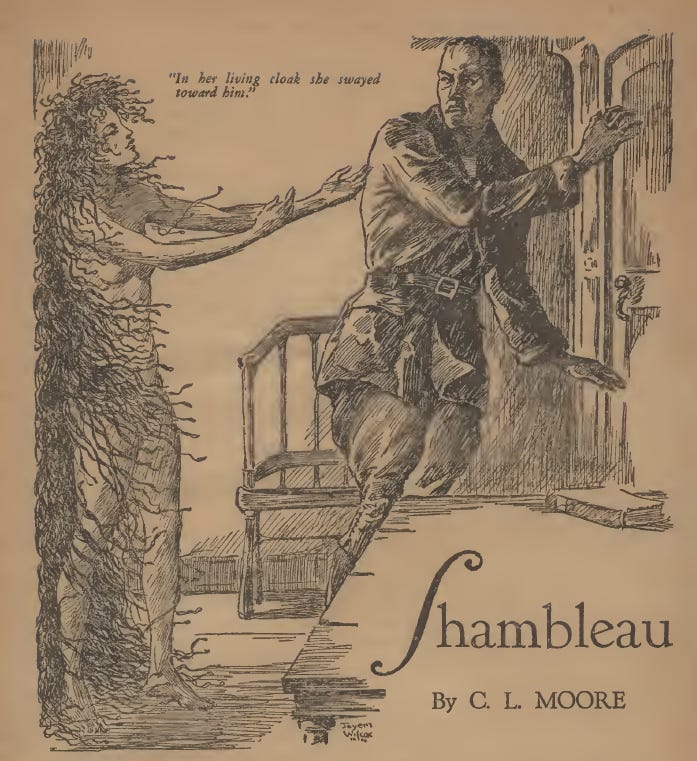

“Shambleau,” published in the November 1933 issue of Weird Tales Magazine, is the first tale of Northwest Smith and it makes for an interesting place to begin asking what genre Moore is aiming for.

If "Shambleau" is any indication of the direction that future Northwest Smith tales will wander, Moore's tales of Smith belong firmly in the genre of Space Opera and completely outside the bounds of Planetary Romance. Though the Smith tales' inclusion of imagery associated with "Weird Fiction" marks them as stories that extend the boundaries of the traditional Space Opera tale. This expansion makes room for later Space Opera classics like A.E. van Vogt’s “Black Destroyer” and the film Alien which was partially inspired by “Black Destroyer.”

I think there is much to support the Northwest Smith stories falling into the sub-genre of Space Opera, a genre that some argue includes the Planet Stories tales of Leigh Brackett. However, I believe that the traditional classification of what is a Space Opera lacks specificity and makes Space Opera too broad a category. If we examine David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer's The Space Opera Renaissance for a working definition of space opera, they offer two early definitions of the genre. These early definitions are more useful in evaluating what genre the Northwest Smith tales belong in. This is because the publication of the Smith tales comes long before many of the tales described by newer definitions. These newer definitions bring to mind epic tales like Iain Bank's "Culture" stories or Asimov's "Foundation" due to conceptual creep leading to an expansion of the use of the term Space Opera.

According to Hartwell and Cramer, the Fancyclopedia II had the following definition:

Space Opera ([coined by Wilson] Tucker) A hack science-fiction story, a dressed-up Western; so called by analogy with "horse opera" for Western bang bang shoot ‘em up movies and "soap opera" for radio and video yellow drama.

Hartwell and Cramer are quick to point out that this definition is actually a watered-down version of what Tucker actually said in his fanzine, which wasn't to actually equate Westerns and Space Opera as telling similar tales. But the connection had been made and by the early 1950s, Galaxy magazine was firm in its use of space opera as "any hackneyed SF filled with stereotypes borrowed from Westerns." The definition of what constitutes space opera has since expanded significantly since the 50s -- it has come to be so broad as to include both Planetary Romance and the "Culture" stories which is almost too broad -- but the connection between the Western and space opera seems particularly significant in the case of Northwest Smith. I would not call Moore's writing hackneyed, but "Shambleau" could easily be rewritten as a Western with only minor cosmetic changes as we’ll see from my relatively close reading of the story.

Reading ‘Shambleau’

"Shambleau," was not only the first tale of Northwest Smith, it was was C.L. Moore’s first published story period. As mentioned above, it was published in 1933 during the height of the pulp era. The shelves were filled with a wide array of writing of various qualities, but it is easy to see why Moore's piece was selected for publication in the November 1933 edition of Weird Tales. The piece could also be used as a demonstration for how to mold a work of writing to suit a particular publication. It isn't hard to believe that Moore actually started this as a Western and then adapted it to better suit the tastes of Weird Tales, an argument strengthened by the fact that Moore went on to write episodes for the Western television shows Sugarfoot (5 episodes), Maverick (1 episode) , and The Alaskans (1 episode).

"Shambleau" opens with a prefatory paragraph which sets the tone of the tale, establishes a sense of history and place, and gives readers some foreshadowing regarding the turn the tale will take. The paragraph is reminiscent of the paragraphs Robert E. Howard used to open his Conan tales. Where Howard’s paragraphs represented excerpts from the fictional Nemedian Chronicles, Moore's resemble the careful tone of a campfire tale. The paragraph is different in tone from Howard's, but serves much the same purpose.

It begins:

MAN HAS CONQUERED Space before. You may be sure of that. Somewhere beyond the Egyptians, in that dimness out of which come echoes of half-mythical names -- Atlantis, Mu -- somewhere back of history's first beginnings there must have been an age when mankind, like us today, built cities of steel to house its star-roving ships and knew the names of the planets in their own native tongues--

One might believe after reading this paragraph -- especially since the place names for Mars and Venus used later in the story are those used in this paragraph -- that he or she is about to read about Space travel in this time before time. This is not the case. References to "New York roast beef" and a "Chino-Aryan war" leave any speculation that this tale takes place in a forgotten time behind. No...this tale takes place in our future, after mankind has once again conquered Space. The sense of the mythical is used in order to make the twist of the story plausible and ensures that the twist falls well within a reader's suspension of disbelief.

We know that our tale take place at some time during mankind's Space conquering future, but what kind of future is it and what kind of man is our protagonist? Apparently, the Mars of the future is a lot like Virginia City.

"Shambleau! Ha...Shambleau!" The wild hysteria of the mob rocketed from wall to wall of Lakkdarol's narrow streets and the storming of heavy boots over the slag-red pavement made an ominous undertone to that swelling bay...

Northwest Smith heard it coming and stepped into the nearest doorway, laying a wary hand on his heat-gun's grip, and his colorless eyes narrowed. Strange sounds were common enough in the streets of Earth's latest colony on Mars -- a raw, red little down where anything might happen, and very often did.

Moore gets us into the action quickly. After the prefatory paragraph sets the tone and place, she launches us straight into a dangerous situation. It's like reading the scrolling preface before a Star Wars film and then being thrust right into the action. In this case, the action of the tale is simple enough. A wild mob is shouting for the death of a woman, whether "Shambleau" is her name or the name of her people has not yet been made clear, and Northwest Smith takes it upon himself to calm the mob and save the girl. The scene reminds me of the opening scene of Deadwood where Seth Bullock confronts a mob. It has a much different outcome, but it’s very much a Western tale trope.

It is only after saving the girl that Northwest Smith comes to understand why the mob was after the woman in the first place -- to tell you more about the girl would be spoiling the fun, but it would also be unfair to leave out further discussion of our protagonist.

We know by Moore’s introduction, and his hand on his heat-gun, that Northwest Smith is a dangerous man. We come to find out that his saving of the woman probably had little to do with chivalry, but more to do with "that chord of sympathy for the underdog that stirs in every Earthman." This chord of sympathy must stir strong in Smith, because the mob is pretty persistent and Smith -- like Han Solo after him -- isn't the kind who wants to get too involved in this kind of action. Smith's business is usually of a different sort:

Smith's errand in Lakkdarol, like most of his errands, is better not spoken of. Man lives as he must, and Smith's living was a perilous affair outside the law and ruled by the ray-gun only. It is enough to say that the shipping-port and its cargoes outbound interested him deeply just now...

Apparently, Smith is a blackguard whose day to day business is so unseemly that Moore refrains from sharing it, likely because the audience would lose sympathy towards our protagonist. It is easy to see how Smith became the archetype that anti-heroes would be based upon for decades to come. He's a cautious man, who pulls for the underdog, but who participates in business best left unspoken. Sounds like Han Solo to me...or Wolverine.

"Shambleau" is a fun tale with a nice twist, a twist that is fairly obvious after the prefatory paragraph and is given away by the Wilcox illustration. The twist, like much of Moore’s fiction, touches on the connection between sex, sexism, and power.

If you want to see more illustrations of "Shambleau" beyond the Wilcox one above, you can see several illustrations from Barbarella creator Jean-Claude Forest at this fairly NSFW link.

I highly recommend reading Moore's prose. Moore incorporates classic mythology into the Science Fiction narrative smoothly and dramatically. Her writing is addictive and she manages to take a classic monster and turn it into something really weird.

![Geekerati: [Blogging Northwest Smith] "Julhi" Geekerati: [Blogging Northwest Smith] "Julhi"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7b54dada-a157-4fea-88ad-e9b01112f431_500x630.jpeg)