Film Review -- Winchester '73 (1950)

Anthony Mann and James Stewart's First Partnership is an Interesting Commentary on Morality

A Grittier James Stewart?

“Hell, I don’t think the leading newspaper reviewers even go to see most of the Westerns. They send their second string assistants. And their supposed to be very nasty and very funny in their reviews. Well it’s a shame, because it makes it a crime to like a Western.”

— John Ford, 1964

Winchester ‘73 (1950) marks the first of nine films that James Stewart would make with director Anthony Mann. Of these films, five were Westerns and critics often discuss how Mann’s Westerns featured grimmer and more morally ambiguous characters than the roles James “Jimmy” Stewart was known for playing. For many, it’s hard to imagine Mr. Smith, Elwood P. Dowd, Alfred Kralik, or George Bailey as a narrowly focused avatar of vengeance or even as an amoral bounty hunter.

It’s less hard to imagine for fans of the Thin Man films. In After the Thin Man (1936), Stewart was cast specifically to play off of audience’s expectations of him being a nice guy. Instead, he portrays one of the best villains of that series. Cynics like me who ironically present the hot take that Mr. Smith is actually the villain of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and who genuinely believes that George Bailey isn’t a nice person at all, have a much easier time accepting Stewart in more morally ambiguous roles. The fact is that as likable as Stewart is in all of his roles, he’s a skilled actor who has long brought moral complexity to his characters.

I don’t think it is that Stewart is playing these darker, almost noir roles in some cases, that is what makes the Mann-Stewart Westerns stand out. I think what modern critics and audiences are responding to is that Stewart is playing a morally ambiguous character, in a Western. Westerns aren’t supposed to be sophisticated narratives after all. In the minds of many critics, they were merely “horse operas” that were devoid of real depth.

In a March 1964 Cosmopolitan interview with Bill Libby, director John Ford responded to these kinds of criticisms. He said, “The people who coined the awful term ‘horse opera’ are snobs. The critics are snobs. Now, I’m not one who hates all critics. There are many good ones and I pay attention to them and I’ve even acted on some of their suggestions. But most criticism has been destructive, full of inaccuracies, and generalizations. Hell, I don’t think the leading newspaper reviewers even go to see most of the Westerns. They send their second string assistants. And their supposed to be very nasty and very funny in their reviews. Well it’s a shame, because it makes it a crime to like a Western. Sure, there have been bad and dishonest Westerns. But, there have been bad and dishonest romantic stories, too, and war stories, and people don’t attack all romantic movies or war movies because of these. Each picture should be judged on its own merit. In general, Westerns have maintained as high a level as that of any other theme.”

Fans and scholars of Western films know that there have been many fine entries in the genre that go well beyond the stereotype. John Ford’s archetype establishing film Stagecoach (1939) has a number of complex characters incorporated into a very simple narrative. But Stagecoach, like Destry Rides Again (1939), came toward the end of the first wave of Westerns. Stagecoach attempted to exemplify what was great about those old Westerns and it succeeded. Destry Rides Again attempted to parody those earlier films. It too succeeded. But like the best parodies, it also ended up becoming one of the best exemplars of the genre and this is is one reason it helped inspire Blazing Saddles (1974).

Just as Stagecoach and Destry Rides Again marked the zenith of a prior era of Western films, Anthony Mann’s Winchester ‘73 marks the transition from the white hat/black hat era of heroes and villains into one influenced by the noir films that began to dominate the box office in the 40s and 50s.

I say that Winchester ‘73 marks a transition from the classic Western to something new because it is a film that incorporates numerous tropes from the older Westerns and then uses the symbolism attached with those tropes as cues that something a little different is going on in this particular film.

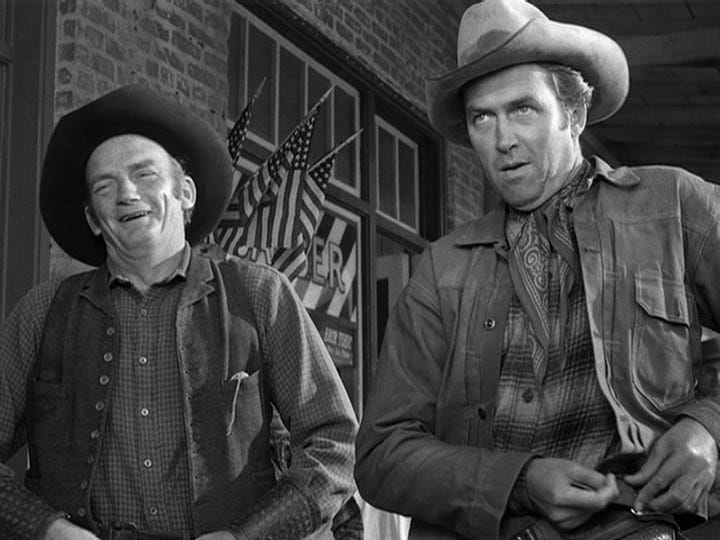

The first, and probably most iconic of those tropes, is the way that Winchester ‘73 uses the white hat/black hat dynamic as a way of introducing its audience to its anti-hero. When Lin (James Stewart) and his companion High Spade (Millard Mitchell) walk into town asking if anyone has seen a man called Dutch Henry Brown, Lin is wearing a white hat. It’s a white hat that is stained with sweat giving it an overall gray appearance. This is a good man who has been pushed to the limit and that has led him onto his quest for revenge. High Spade, his sidekick, is wearing a black hat. So too are Dutch Henry Brown and Marshal Wyatt Earp.

Speaking of Wyatt Earp, Will Geer makes for one of the most unique versions of the character to hit the screen. Geer’s portrayal has an almost comedic quality to it and the Earp of Winchester ‘73 is not hero. He and his brother may be “the law” in Dodge, but they aren’t much of it and Earp seems more comfortable fraternizing with Dutch than he does with Lin. It’s a take on the character that is suggestive of the complexity of the real Wyatt Earp and that predicts more morally ambiguous portrayals of the character that will come later in Hour of the Gun (1967), Tombstone (1993), and Wyatt Earp (1994).

Earp is not a hero in any form in this film, a fact slightly surprising given that the film’s story credit is Stuart N. Lake and he was the major promoter of the Earp story. In Winchester ‘73, Earp is a catalyst of a sort, the shooting contest he runs is how Lin acquires the eponymous Winchester ‘73, but when that gun is stolen Earp plays no part in the attempts to regain the weapon or to uphold the laws that Dutch Henry Brown has broken. I won’t go into Dutch’s crimes here as those are a reveal worth discovering narratively. The film may be over 70 years old, but a review should be more than a synopsis.

While Dutch’s crimes are the inciting incident that lead Lin to Dodge City, it is Lin’s loss of the Winchester to Dutch that is the inciting for the audience. An incident that splits the narrative into two storylines that diverge and converge several times over the course of the film as the gun makes its way from one owner to another. This continual shifting of ownership of a perfect “1 of a 1,000” Winchester rifle allows the film to introduce an interesting array of characters, but it is the way it is done that is most facinating.

Because the Winchester moves from one owner to another, the film’s narrative flow feels less like a single story than it does a series of vignettes united by a single through arc. The through line is Lin’s quest for revenge as he pursues Dutch up and down the central United States, the foothills and plains that come prior to the Mountain West. This through line intersects with several vignettes where various characters encounter and acquire the Winchester rifle before it, like the One Ring finally finds its way into the hands of its true master.

Each of the vignettes of the film is a moral commentary on what it means to be a virtuous person in a lawless land. Who upholds the good when there is barely a society to enforce mores?

The first vignette is the gun shooting contest wherein the best shot in Dodge City will win the perfect rifle and the key focus for moral critique here are the Earps. Wyatt is morally suspect and Virgil is nigh incompetent. As Marshal of Dodge, one would expect Wyatt to enforce the law not just in Dodge, but in the surrounding area as well, but he has no real interest in that. He just wants to keep Dodge calm and he does that in a style that cozies up to the black hats. Once Lin is ambushed and the Dutch has stolen the gun, Lin’s pursuit becomes double pursuit. He wants both to get his revenge and to be made financially whole by the return of his weapon, but his driving focus is revenge. In Anthony Mann’s West, it is up to the individual to enforce the rules of justice (a trend that continues through all five Mann-Stewart Westerns).

Each of the vignettes that follow provide commentaries on the conflict between liberty and license, civilization and lawlessness. The first vignette focuses on avarice and gluttony and intoxication all of which lead to the loss of the weapon to a crooked gun trader. The second deals with economic exploitation and shows what happens when you don’t have law to defend contracts. You have bad faith actors like the gun trader who come to a bad end because the only guarantee of contracts being upheld in a lawless society is to kill those who violate them. This is followed by a really interesting analysis of marriage and family in the untamed West and Shelley Winters performance as a prospective frontier wife, and the cowardice and villainy of the man she had agreed to marry, could make up entire volumes.

Lin’s pursuit of Dutch leads him to come into contact with the aftermath of each of these small morality tales and he judges them as one would expect a moral man to do. He takes no joy in killing for necessity. He knows the costs of cowardice and advises forgiveness. But when his pursuit finally leads him to a place where he can have his revenge, when he re-encounters a Shelley Winters character who has succumbed to despair and is now accompanying a true villain, he is finally given the opportunity to release all of his rage. First he releases it on one of Dutch’s henchmen and finally gets to try and have revenge on Dutch himself, all while still trying to maintain a level of respect for civilization. He’s a white hat, to be sure, but he’s a white hat stained gray with the strain of moral conflict. Does he save someone or get revenge? Does he uphold the principles of law and order or does he focus on revenge?

In Anthony Mann’s vision of the West, there is only one answer to that question. Revenge comes first, especially when it is vengeance guided in re-establishing moral order, only then will families be safe. Only then can civilization be built.

I highly recommend the film. It has some elements that date it, badly, but it is a morally complex Western with interesting characters. They aren’t quite as realistic as the characters in later Westerns will be, but this film marks a real transition from a more fairy tale Western to the more morally complex Westerns of Budd Boetticher (Seven Men from Now, Ride Lonesome), Sam Peckinpah (Ride the High Country, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid), and more recent directors.