Heroes of Karameikos First Steps (Attributes)

Old School Meets New School with some early thoughts on the mechanical assumptions of each game.

Last week, I mentioned that I’ve been working on a set of house rules for Basic/Expert D&D, lovingly called B/X or Moldvay/Cook D&D, that incorporate some of the feel of 4th Edition Dungeons & Dragons. I’m very excited about the project and have already begun work, but it’s important to examine what assumptions from each edition I want to leverage to create a set of rules that fosters the kind of play I want.

After all, I’m looking to create a game that has “4th Edition Feel Using 1st Edition Rules.” Thanks to my friend George Strayton I had the chance to work on a project that was trying to make 4th Edition feel more OSR. This time, I’m going the opposite direction and so I want to walk with care. To do that, I’ve been thinking about some of the underlying assumptions of each edition and how I want to balance them. I’m going to present a few and I’d love to get your feedback.

Ability Scores

Ability scores don’t matter as much in Old School D&D as they do in post-3rd edition games. Sure, having high scores in Strength or Dexterity mattered for fighting characters and Charisma was surprisingly underrated (see below), but the underlying math of the game didn’t assume you had great scores. The modern game is very different. The scores matter a lot and are a part of the underlying assumptions of determining task difficulty. This is true in 5th edition, but it was even more true in 4e.

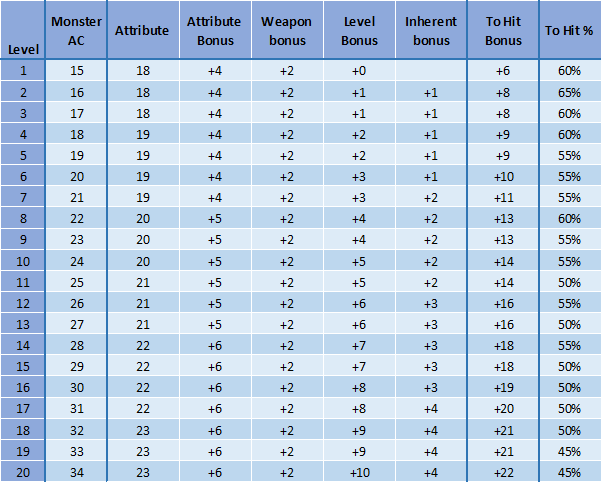

There’s been quite a bit of writing about how 5th edition relies on “Bounded Accuracy”. Essentially Bounded Accuracy is a concept of whether or not a character hits is constrained within a range and that it’s the amount of damage done that varies per level. In 5th edition the bounds are that there is a maximum AC of around 27 and the most difficult that a skill challenge become is a difficulty class of 30. Those numbers are outside the range of starting characters, but don’t take long to achieve some ability to succeed at. 4th edition was even more rigid in its bounded accuracy. In that system, characters were assumed to succeed (regardless of level) somewhere between 45% and 60% of the time.

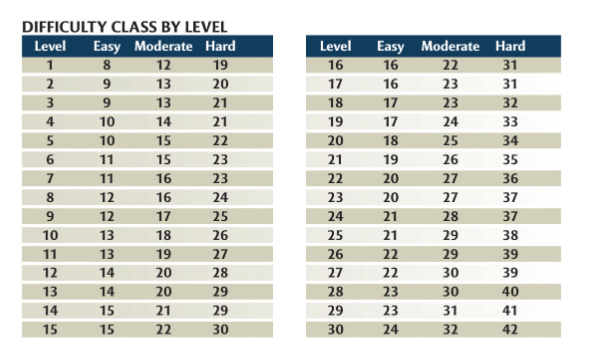

This assumption of a static difficulty being anchored around 50% lead to one of the weirdest mechanics in 4e, the “DC Tier” for skill checks. If you examine the Difficulty Class by level chart, you will notice that the difficulties for “Easy, Moderate, and Hard” tasks increases by approximately one point a level with a couple of stall points. Given that characters in 4e gain effectively a +1 bonus every level from one source or another, this means these difficulties stay static. A Hard task is always Hard and and Easy task is always easy and has the same chance of failure at all levels. This was a big change from 3.x and was a point of contention for many players because it doesn’t make much sense.

My own fix for this issue was to use the three tiers of D&D game play Heroic, Paragon, and Epic and use those as a baseline for finding action difficulties. Instead of having the difficulty class of a skill be based on the character’s level, I had it based on the level of the challenge. Was what the player was attempting a Heroic act that we’d read about it a hyperrealistic Sword & Sorcery novel or was it an absolutely bonkers epic action similar to what a Brandon Sanderson character could do? Was it Warhammer Old World or Warhammer Age of Sigmar? Then I’d ask if it was Easy to Hard for that genre. This meant that there were things players couldn’t attempt at low level because I’d rule them out as “Epic” tier but also meant that I would use lower DCs for an Easy task by an Epic character in a way that felt natural to players who started with 2nd and 3rd edition.

There are a lot of things I like about 4e, but its system of bounded accuracy was too limiting. Wizards of the Coast clearly noticed this because their Gamma World was limited to 10 levels and while 5th edition kept the concept of bounded accuracy it made the bounding distribution much wider. It should be noted that Robert Schwalb also noticed when he designed his Shadow of the Demon Lord game. Schwalb’s game, like 13th Age, is a refining of 4e.

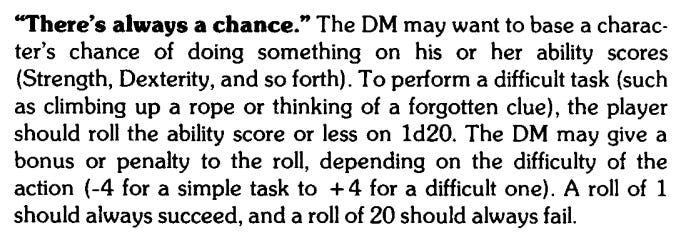

Okay, so stats matter a lot in 4e but what about in B/X D&D? Unlike post-3rd edition D&D games, B/X’s mechanics assume that everyone has average abilities with no bonus. The game also completely lacks a list of skills, other than the percent based Thief skills. The Basic rule book does provide a pseudo skill system with the “There’s always a chance rule,” but it is extremely broad and has a similar problem to 4e in that the probabilities don’t change with level. The player has a chance to succeed based on ability score with a potential modifier.

It might surprise you, based on my critique of 4e’s bounded accuracy rule, that I wouldn’t like this, but I do. I like it for two reasons. The first is that ability scores don’t change in B/X much and that they start lower on average so you’ll usually only have someone exceptional having outside a 60% chance to succeed, a chance that can be modified +/- 20% (or more) based on difficulty. When B/X became BECMI (Basic, Expert, Companion, Master’s, Immortals) D&D, this rule became the basis for the skill system. Since the Mystara sourcebooks introduced the full skill system based on this rule, in The Grand Duchy of Karameikos, I’ll likely be using an adapted form of it. It’s a case where both games have a similar bounded accuracy for skills, but where the difficulty of tasks makes more sense because they are rooted in the attribute directly rather than indirectly through an absurd table.

So…what do we do with ability scores? If we are going to be adding skills, which we are, we want there to be a little more certainty in getting a good one but not too much certainty.

Here’s what I propose:

Just as in 4e, players will pick a character’s class before rolling statistics.

The player then rolls 4d6, taking the best 3, for their prime requisite and rolls 3d6 in order for the remainder of their statistics. Some classes, like Elves for example, have more than 1 prime requisite. In this case, the player would have to pick which prime requisite gets the 4d6 take the best three roll and the other would be rolled normally.

This has a couple of effects. When combined with the skill system, it makes it more likely that a character of a chosen archetype will be better at skills related to that archetype. Second, it makes it more likely that characters will get an experience bonus for their class. This system also keeps a balance between old school and new school feel by allowing heroic characters to be more “normal” everywhere else.

I should note one thing about Basic D&D, which is hinted at in the comment about Charisma above, and it’s that there are not really any “dump stats” in B/X. Every attribute matters for every class. They may not matter as much as post-3e games, but when they help they help regardless of class. Charisma is the biggest one here. It’s not the prime requisite for any core class (though it will be for at least one class in my project). It is however, arguably, the most powerful attribute in the game. B/X games incorporate a “reaction” table for encounters with creatures and NPCs who aren’t automatically hostile, which really only should include Undead and some highly motivated foes of other sorts. This means that a party with a high Charisma character can have a lot of victories without ever fighting. Imagine if you will playing Keep on the Borderlands, but using the conflicts within the Caves of Chaos to your advantage via the use of Charisma. That’s something that wasn’t done near enough when I played as a kid, but was definitely rules as written.

This Reaction Table has got me thinking about how skills should be executed in my B/X hybrid, but that’s food for the next entry.

What are your thoughts on the attribute question? I need to discuss more about the particular benefits of each attribute before we can answer that, or do you already have thoughts? Feel free to share.

Cool, can't wait to hear more