The British Wargaming Scene and Role Playing

It’s the 50th Anniversary of the Dungeons & Dragons role playing game and we’ve learned a lot about the how the game came to be designed over the past decade. We are finally beginning to recognize the contributions of many who had been forgotten or pushed to the side in the past.

The Secret of Blackmoor documentary covers the story of how one strain of the modern role playing game developed as well as how important the Minnesota Wargaming scene was in the creation of Dungeons & Dragons and the role playing game hobby. Particular importance is given to the quasi-roleplaying events created by David Wesely around 1969 called Braunsteins which the Minnesota Scene argues are the foundation of modern roleplaying games. One way of describing these events is as a combination of postal Diplomacy, traditional Wargaming akin to Strategos, and childhood storytelling games. They were truly innovative and were undeniably a direct antecedent to Dungeons & Dragons, especially with regard to the role playing of characters and the playing of campaigns that continued session after session.

The role that David Arneson and his gaming community played in the development of role playing games had too long been hidden in the shadows of Gary Gygax and it's fantastic to see a focus on the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons. However, I think a focus on Arneson as the “true creator” of D&D can make us forget the fact that role playing games were a "perfect storm" of gaming influences coming together and that many of the things that were happening in the Minnesota Wargaming scene were happening elsewhere as well.

In the case of the British Wargaming scene, gaming and gaming related developments were happening in a way that also influenced the invention of Dungeons & Dragons and that provided a fertile field of consumers in the UK when the game finally came to the shores of Albion.

When it comes to Miniatures Wargaming, in both the US and the UK, there are a handful of names that loom large and are the wargaming equivalent of Gygax & Arneson: Tony Bath, Donald Featherstone, Jack Scruby, Charles Grant, Donald A. Wollheim, and Captain J.C. Sachs. Not to mention the influence of H.G. Wells, Robert Louis Stephenson, Peter Cushing, and "Cass and Bantock" on the hobby.

I mention all of these people in the British wargaming scene not to take away from the influence that David Arneson and his group had on Gygax and D&D, but to point to another group that had an influence on both Arneson and Gygax. The miniatures wargaming community in the mid-20th Century was small and gamers communicated with one another across the "pond." The fact that Gary Gygax had an article published in Donald Featherstone's Wargaming Newsletter two years before the publication of D&D is proof that they were in communication with one another, or at least that the UK scene was an influence on Gygax's gaming. We also know that Gygax and Perrin's Chainmail rules were influenced by Tony Bath's 1956 and Phil Barker's 1966 rules for Ancient and Medieval Wargaming. The fact that Barker's rules were published in a 1966 copy of the Wargamer's Newsletter suggests that Gygax had been reading the magazine for some time prior to his published article. Steve Curtis’ Western Gunfight rules show that English gamers were similarly thinking beyond “winning” and wargaming and about portraying individual characters.

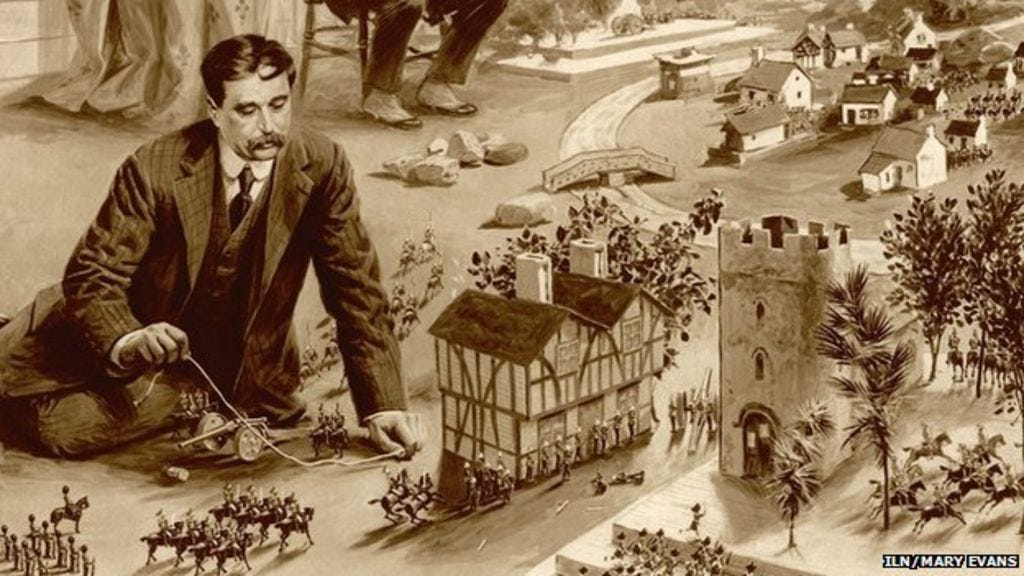

But let's take a step away from the direct influence and merely look at the development of wargaming in the UK on its own. The original recreational wargamers, at least in published form, are H.G. Wells and Robert Louis Stephenson. Wells' rules were published, but they bear little mechanical resemblance to modern role playing and wargaming. Casualties in Wells' game were determined via the shooting of a toy cannon and not the roll of dice. If you want to check out the game and play it with its original rules, or with new ones, I recommend the recent Paper Boys edition.

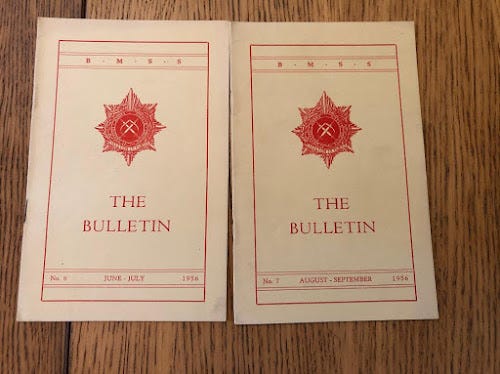

There are a number of wargame rules that follow in the footsteps of those designed by Wells. Reading through issues of the British Model Soldier Society Bulletin provides several examples of people shooting down enemy troops. But British wargaming wasn’t limited to the simulation of real battles or the shooting of miniatures with pea shooters.

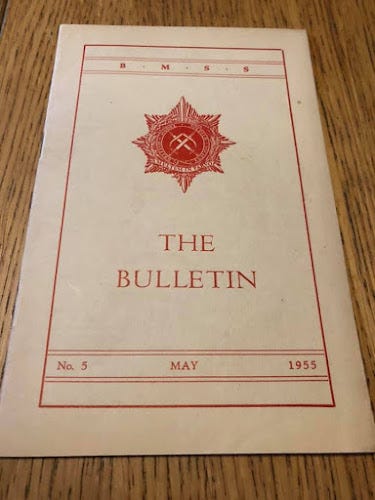

Charles Grant provides the best description of how wargaming in the UK was evolving in a way that included many of the same types of play that would result in D&D. In the May 1955 British Model Soldier Society Bulletin, Charles Grant discuses the state of wargaming at the time in his article "The War Game -- Past, Present, and Future."

His account is highly personalized, but it matches many descriptions of the development of the hobby. His wargaming journey began with "casualties being inflicted by means of a table top tennis ball" and eventually shifts to the British Model Soldier Society's rules when he was older and began to reenact Napoleonic campaigns. It's interesting to note that these rules, which I have yet to locate, mark the beginning of a shift away from using some form of real world projectile to determine casualties as Grant states, "these games were more or less based on the Society's rules, the exception being that, having regard to the quality of the troops engaged, no actual firing took place..." It is at this point that Grant begins to calculate losses.

He describes how soon after his shift to Napoleonics he began playing in games of another sort. This is where we begin to see real parallel developments in the UK hobby to what would eventually happen in Minnesota. Grant states that on one occasion, "a three-handed game was played [with] a certain amount of diplomatic prelude being necessary. Never were there such Machiavellian machinations...and when the three armies finally met in battle, each contestant was firmly convinced that he had at least one ally!" This description suggests that there were proto-roleplaying elements being inserted into Grant's gaming, thanks to his friend Peter Young, and that it was only the very real Campaign of 1939 (the beginning of WWII) that provided the reason that "the protagonists had to go their separate ways." Grants descriptions in 1955, of his pre-1939 gaming, very much sound similar to that of Arneson's Braunsteins. Once again, this is Pre-1939 gaming. Here are an example of how role playing campaign elements appeared to enter play, "On the historic occasion when one Hess parachuted on to my native soil (likely this event) I received notice from my enemy that a certain Murat had been picked up, having dropped from a balloon 'somewhere in Austria!'" Grant also discusses how his group changed the rules to classify wounded in a manner that added "verismililitude to one's bases and lines of communication."

Two things are made abundantly clear by these examples. First, that Grant and his fellow gamers were playing campaigns similar to what modern roleplayers or wargamers would understand. The fact that their "Campaign of 1805" resulted in very different combats from those in history, combined with the fantastic tale of Murat's balloon drop, suggest that the Grant games engaged in a level of roleplaying, even before they began to incorporate dice into play.

Grant goes on to mention the use of rules developed by "Captain Sachs," though those appear to still require the use of actual projectiles for casualties. It isn't until Grant encountered the "Bantock" rules, probably the Bantock-Cass rules Donald Featherstone mentions as being influential to Tony Bath, that Grant begins to favor wargames that use die to determine outcomes. Grant went on to become one of the major figures in wargaming and it's interesting to see how much "roleplay" existed in the hobby as a whole. We'll see more of that when I discuss Tony Bath's writings in the 1956 Bulletin and his famous Hyborian Campaign.

Before I move on though, I'd like to note again that Donald A. Wollheim was an active participant in the British Model Soldier Society. The reason I'm taking the time to highlight this is that Wollheim was a major US Fantasy and SF publisher and was (in)famous for bringing the first paperback printings of Lord of the Rings to the US with his "Ace" paperback versions. Gary Gygax may have stated that Tolkien had very little influence on D&D, but Tolkien’s books were certainly admired by at least one American wargamer.

What I find striking in all of this is the deep connections between wargaming and Fantasy as the hobby developed. From Bath's Hyborian campaign, inspired by Robert E. Howard's Conan, to Wollheim's membership in the BMSS, an active gaming community, the ties are there from the start and they span the Atlantic.