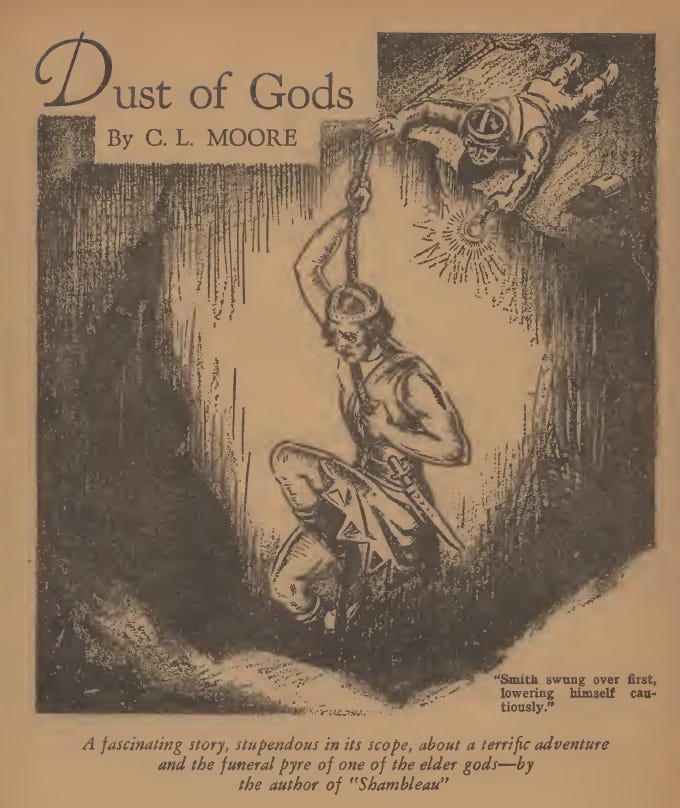

Blogging Northwest Smith: Dust of the Gods

An Examination of C.L. Moore's Fourth Northwest Smith Story

"I have graven it within the hills, and my vengeance upon the dust within the rock." -- Edgar Allan Poe, Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym

Catherine Moore's fourth Northwest Smith story is one which continues a noble tradition in Weird Horror fiction, the Antarctic/Arctic expedition. This particular tradition has included some of my favorite horror and science fiction tales and movies. A list of stories in this vein includes Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, Edgar Allan Poe's Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness, John W. Campbell's Who Goes There?, and John Carpenter's The Thing, based on Campbell's tale. These stories combine mankind's natural curiosity, the desire to explore the unknown, with mankind's natural fear of that same unknown. Given the lifeless wastes of the Antarctic/Arctic environment, it is the perfect setting for a scary story.

Arctic and Antarctic wastes are particularly rich locations for the "post-mythological" horror story, the kind of horror story that leaves superstition and mysticism to the dust bin of history and creates supernatural horror that might exist in a rational and material universe. This is the perfect horror for a scientific age. Kenneth Hite, in his Tour de Lovecraft entry for At the Mountains of Madness describes this kind of tale as "remythologization." According to Hite, remythologization is a style of horror that provides a "plausible entryway for 'adventurous expectancy' not through a world-view that saw everything as magic but through a new world-view, one that saw everything as rational." It is horror for a world where "God is Dead," and where traditional spooks don't provide the chills they once did.

One can also see a parallel line to remythologized horror in something I’ll call post-mythological horror. Post mythological horror can be seen in film franchises like Saw, Hostel, Last House on the Left, Manhunter (big time), and Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Films like these, themselves descendants of Grand Guignol, provide the shocks and chills that thrill the imagination without the need of "mystical" events. Those films focus primarily on personal horror though where Hite’s concept of remythologizing horror contains things that make us afraid of the dark in general and not those that make us fear our fellow man. This concept is at the core of “Cosmic Horror” which focuses on the fear of the unknown that exists within people.

A great example of the process of remythologizing horror is the, soon to be remade, Blair Witch Project. The film comes from a distinctly materialistic position as young people seek to investigate a ghost story in the same manner that shows like Ghost Hunters do. Most of us know that those shows don’t actually encounter any supernatural and that kind of “investigation” has been parodied many times in shows like Supernatural and even in the recent Emma Roberts film Space Cadet.

The “investigators” in Blair Witch Project disappear and we, the audience, only know their story because of “found footage” left behind that shows us their experience. While the film itself used a remythologization process, the marketing campaign was were we as an audience really saw this phenomenon. In many ways, the marketing campaign built the real horror I experienced as a viewer. It was only in the context of the marketing myth around the found footage that the film really grappled with my subconscious and led to a real sense of dread, hours after watching a film I found tame during the viewing.

Human-o-centric tales of murder like Saw are horrifying but they are different from the remythologized horror depicted in the Antarctic/Arctic expedition tale and movies like Blair Witch Project, but there are key differences between the Antarctic/Arctic expedition tale and Blair Witch Project in how they remythologize the supernatural. In Blair Witch, the witch turns out to be a real threat. The Blair Witch-verse is one where we stopped believing in the supernatural, but the supernatural didn’t stop believing in us.

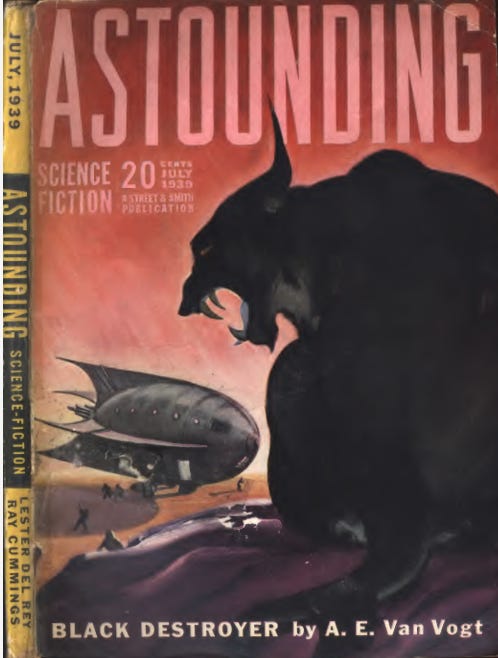

The Antarctic/Artic expedition tale is different, it still includes elements of the "supernatural,’ but it is only "supernatural" in the sense that what is encountered goes beyond what we currently understand about nature. The supernatural element isn't something that violates the laws of nature, rather it is something that man has yet to encounter that evolved according to the laws of nature in a manner different than previously encountered. Poe is the possible exception here -- the one that proves the rule. Like the Xenomorph in Alien, the creature in Star Trek’s The Man Trap, and the Couerl of A.E. Van Vogt's Black Destroyer (which are expedition tales that substitute space for Antarctica), the unstoppable horrors are material and not mystical.

This is a fun genre and it is nice to see Moore dip her toes in with "Dust of the Gods."

"Dust of the Gods" begins, like many Dungeons and Dragons campaigns and too many fantasy stories, at an "inn" where our protagonist and his loyal companion sit in search of something to do. Northwest Smith and his trusty Venusian sidekick Yarol are broke and down to their last drop of whiskey, a state with which I can deeply sympathize. They are in need of adventure and finances...not necessarily in that order.

While they are commiserating about their lack of liquidity, Yarol notices two men entering the establishment. He describes them as "hunters" to Smith, and hints that they might know where he and Smith can get some work. It doesn't take long for Yarol to notice that there is something different about these two men than Yarol remembers. They are more paranoid than usual. Smith sarcastically proposes that the reason the two men are so skittish is that they may have found what they were looking for and are now haunted by the experience. This is in fact, as it turns out, the case. The two men were hired to go into the arctic regions of Mars to find the "Dust of the Gods" and bring it back, but after finding it have returned to civilization psychologically scarred.

China Miéville argues convincingly in his introduction to Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness that the story was a retelling of Poe's Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, and not in any way a sequel. I think he is right, but I would argue that Moore's "Dust of the Gods" is a sequel to both the Lovecraft and Poe tale. It is also, if Miéville's account of the politics of Lovecraft's tale is correct, a political response to the Lovecraftian version. The two "hunters" are the men who have returned from Lovecraft's Antarctica forever changed by the experience, Lovecraft's Antarctica has merely been moved to Mars so that Northwest Smith and Yarol can follow in the footsteps of those who have been broken, like Lovecraft's Danforth and Poe's Pym, and succeed where the others have failed. Smith seeing once brave men, now jumpy and frightened, has intrigued his own sense of adventure. He wants to know what could shatter the psyche's of once brave men.

Smith doesn't have to wait long, for he is quickly approached by an old man of indeterminable ethnicity. His features are described as follows, "under the deep burn of the man's skin might be concealed a fair Venusian pallor or an Earthman bronze, canal-Martian rosiness or even a leathery dryland hide." The old man's ethnicity is obfuscated by time and wear (an important contrast to the clear black/white dichotomy of both the Poe and Lovecraft version).

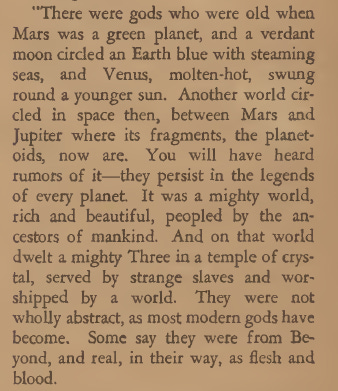

It turns out that the old man is the person who hired the other hunters and that they indeed found what they were seeking (or at least "where" they were seeking), but that they failed to return with a “treasure” the old man seeks. Smith and Yarol listen as the old man gives them his sales pitch. He wishes Smith and Yarol to travel to the arctic in search of the remains of the god Black Pharol, of whom all that remain are a pile of dust. Pharol was one of the three original gods, on whom all others are based, and the only one to leave behind any physical essence. As the old man describes them:

In one paragraph Moore has transformed a theological construct into an alien and material one, following very much in the footsteps of Lovecraft by making her "gods" ancient trans-dimensional aliens. This also falls in like with what Lucretius does in De Rerum Natura where the gods live only in the spaces between and not in our world. The first two ancient alien gods, Saig and Lsa, disappeared so long ago that not even legends of them exist, but Pharol who was "a mighty Third set above these two and ruling the Lost Planet" continued to exist after the other two had faded away. Eventually Pharol too passed from this dimension leaving behind a pile of dust that still contains some of his essence, and which the old man seeks so that he can reach Pharol and control him. The old man knows that for "the man who could lay hands on that dust, knowing the requisite rites and formulae, all knowledge, all power would lie open like a book. To enslave a god!"

For some reason, that old man's maniacal declaration doesn't dissuade Smith and Yarol from taking the job. Apparently they are desperately in need of money and the whiskey it can buy, desperate enough to risk madness. Besides, if you're drunk enough are you really going to notice the primordial extra-dimensional god destroying the universe as you know it? Smith and Yarol accept the man's offer and travel off to the arctic to find the dust remains of an ancient god.

They eventually arrive at a range of mountains in Mars polar region and follow the directions the old man gave them, where they discover a passage leading under the surface of the planet and, if the old man is right, into the heart of the crystal temple that once was home to the Three gods.

As they pass through the tunnels, they encounter two phenomena that are references back to the earlier Poe and Lovecraft tales. First, they encounter a darkness that is impenetrable. Their space age flashlights cannot penetrate the darkness and it is an almost palpable thing. In a way, Moore's inclusion of a physically palpable darkness is reminiscent of Poe's inclusion of dark people in the Antarctic regions, only here Moore refrains from the racist undertones of Poe and Lovecraft by having the darkness itself alive and no more terrifying than the next "thing" to appear. That thing is a white apparition reminiscent of the figure at the end of Poe's Pym. Smith and Yarol are able to determine that this white figure is what the two original hunters fled from and it is this that they fear is chasing them.

It should be noted that while Poe's Narrative ends abruptly with the appearance of a white apparition, it is the narrator's recalling of this apparition that likely causes his untimely death and thus inability to finish the tale. Poe's readers never find out what happened next because the narrator dies, likely from fear, during the retelling. One might say that Smith, after he encounters and passes Moore's white apparition, is continuing where Pym left off. He is certainly continuing beyond where the hunters explored. The appearance of the white apparition pulls on Smith's psyche, but he manages to retain his connection to reality and leap past the apparition and "fall" deeper into the planet. Smith eventually speculates that the apparition may only be able to exist in the palpable darkness.

When Smith and Yarol do find the crystal temple and open its doors, they have yet more one wonder revealed to them. The crystal temple is illuminated by light that behaves like a liquid and their entry has provided a whole by which the light can drain from the room like a crack in an aquarium. This light is the true counterpart to the darkness described earlier and the description of it draining from the room is one of the most interesting descriptions I have read in fiction for sometime. I might venture to say that the concept of "liquid light" is one of the more original ideas I've read.

As the light drains from the room, Yarol walks up to the triple throne and finds the dust of Pharol and is about to pack it up for delivery when he picks up on Smith's thoughts that it may not be the best idea to give a madman this kind of power. They had initially written the "power" of the dust off as superstition, but their journey has made them think better of it. Smith and Yarol finally make their first "moral" decision to date in the NW stories, they decide to destroy the dust if they can. During their attempt, Smith's psyche is overwhelmed as he sees images of the world as it was when it was ruled by Pharol and the others of the Three. He even sees the death of the Lost Planet and realizes that this temple crashed into Mars eons ago where it became a temple for ancient Martians before their civilization decayed and the gods were forgotten. Smith and Yarol leave to return to their lives having encountered darkness, but still whole for the experience.

It is in this ending where Moore breaks most strongly from Poe and Lovecraft. In their tales, the protagonists are broken by an experience beyond their control. In Moore's tale, Smith and Yarol leave having decided to save a world, and possibly a universe, from horror. China Miéville argues that the Shoggoths of Lovecraft's tale represent the "masses" and their decaying effect on civilization. Lovecraft's protagonist has a mental breakdown while in a subway station, reminded by the sounds of the masses around him of the amoeboid horrors in Antarctica. The masses are the horror in Lovecraft, in Moore it is the dictator who is the horror. All Smith and Yarol need do is to stop one man to save mankind, mankind isn't the villain of the tale. "Dust of the Gods" was written in 1934 and the "Enabling Act" that gave Hitler dictatorial control of Germany had been passed on March 23, 1933. One wonders if the rise of the dictator in general, and Hitler in particular, were on Moore's mind as she wrote this tale. Whatever the case it is certain that by focusing on the evil one man is capable of doing, rather than the terror of the mob, Moore was not merely writing a sequel to Lovecraft. She was also writing a political response to him.

It should also be noted that Moore's use of the dust of Pharol seems to be a reference to the final sentence of Poe's Narrative, which is the quote at the top of the piece, and demonstrates how centrally important story titles can be to the literary conversation that authors participate in with each other as history unfolds.

Other Entries in the Encountering Northwest Smith Series

I absolutely love C.L Moore. Great to see some recognition of her work. Fantastic read.

Moore was one of the most accomplished of the Golden Age science fiction and fantasy writers. Her ability to create stunning scenes and resonating language like few others of her time still makes her stand out in this field.