I Liked D&D More Before it Became GURPS

Thoughts on D&D, Mechanical Shifts, and a Skill System for Heroes of Karameikos

“Almost all old school dungeon delving is an off the cuff Player VS DM negotiation made in the moment.” — Jim Zub

What’s with the Clickbait Christian?

Okay, that title was pure clickbait, but it is related to a topic I’ve been thinking about as I work on my Heroes of Karameikos “Old School meets New School” rules set.1 I’ve been wondering how and whether to incorporate some form of skill system into HoK. I’m leaning towards “yes,” but I want to make sure that whatever skill system I create doesn’t limit the way players imagine what their characters are capable of doing.

Some Pre-D&D Discussion Background

Before I get into talking about how D&D became GURPS, I need to talk about what I mean by “became GURPS.” When I say that modern D&D is GURPS, or at least GURPS-esque, what I mean is that it has a very mechanics based mentality. In modern versions of D&D you have a number of skills and/or proficiencies that describe tasks you are good at. In 3.x the list of skills is longer than in 4th and 5th edition and includes “trained only” skills, implying that there are some things you can only do if you have training.

When 4th edition came out, the skill list was reduced and “trained only” skills were removed. One of the many negative reactions against 4th edition I saw being stated was that 4th edition more wargame, and less role play, oriented than earlier versions of D&D. The key piece of evidence to the “less role play oriented” argument was often that the game had a smaller skill list and that not having skills reflecting certain actions reduced players’ ability to role play those actions. While I addressed critiques of 4th edition’s combat mechanics being “more tactical miniatures game than past editions” in an earlier post (see the link below), I haven’t addressed the “less role play” oriented argument at all.

I hadn’t addressed this argument before because I didn’t understand where it was coming from. My thought process was “why should having a smaller skill list reduce the amount of role playing opportunities?” It didn’t make sense to me and my experience running 4th edition games was one filled with countless memorable role play moments. It wasn’t until I began to think back on the history of role playing games, and my experience playing the Champions role playing games with a group at CalTech, that this critique began to make sense. I have since come to call this critique a “mechanics based mentality.”

What is a Mechanics Based Mentality and How Can a Game Design Minimize it?

I shared some of my concerns regarding a “mechanics based mentality” in my February 9th Weekly Geekly.

wrote about this mentality in his review of Metamorphosis Alpha on his Indie RPG newsletter. In that review, he discussed how not having specific skills seemed to imply to many modern gamers that their character couldn’t do an action. The example he gives to highlight the challenge for some gamers is that, “it was honestly like playing a PbtA game with four very specific moves and nothing else.”It was interesting to me that he highlighted Powered by the Apocalypse games in particular because one of my personal objections to games that are Powered by the Apocalypse is that these games might teach players that their characters can only do what is on their sheet. The very “term of art” use of the word “moves”, instead of “actions,” in the game and the way that these moves are described can be presented in a manner that suggests to players that these moves are the limit of what they can do. Given that in the best PbtA games each playbook’s has a strong connection to the archetype it represents, this can exacerbate this problem. This is especially true if the move under consideration is narrow in concept.

The original Apocalypse World attempts to minimize this in some ways by providing Basic Moves and expanding on what they mean in play. For example, “Act Under Fire” is a move that would be used to react under any kind of pressure. That action could be combat oriented or social. So too can “Go Aggro” be used in a wide variety of cases. Notice that in Apocalypse World there is no “Climb that Shit” move. That’s not the kind of question Apocalypse World is interested in tying to an explicit move and the rule book covers a lot of ways to simulate this. For example, if they had to climb the wall in a hurry (under pressure) then “Act Under Fire” would be a good move. This kind of use would be a negotiation between player and GM. In a PbtA game with more specifically worded moves, especially if it lacks discussion of broader uses of narrow sounding moves, this can become an issue.

Most of the popular PbtA games follow Apocalypse World’s lead and give a good list of basic moves that are broad in description and meant to be interpreted in play to accomplish a variety of tasks. This reliance on movies and the tying of certain moves to archetypes is one way that shows PbtA games have a bit of DNA from the classic indie rpg Over the Edge. Interestingly, Over the Edge also shows us an easy way out of any potential “if I don’t have the specific move can I do it” trap. That solution? If the average person can do it, you can attempt it.

In Over the Edge, instead of picking a character class or playbook players describe their characters using four key traits. These traits are similar to Moves in design and application. When players make new characters in Over the Edge, they choose one of these traits to be rated as a Superior trait, two as Good Traits, and one trait is some sort of drawback. These traits can be anything that the player imagines. For example, superior traits could range from “International Superspy” to “Font Designer.” Any character only get these four traits, but they have absolute freedom to pick them. When they use their Superior trait, they are better at performing tasks related to that trait than almost anyone in the world. They are among the best at that thing. A person who has a Good trait is above average at a thing. As for everything else, excepting their drawback, characters are average.

By including an “average” capability for all tasks, in this case a roll of 2d6, players know that they are never overly restricted in what they can try. Their traits merely make them better at that thing than an average person, and if an average person can do it you can attempt it. Sure, there might be a trait called “Laser Vision Eyes” that implies only having that trait allows use, but there might also be a trait called “rock climber” that only signifies that the person is better at that thing than average.

Assuming all characters can do anything that an average person can to is something that should be a baseline assumption in any game, regardless of how big or small the skill list of the game is. Even if Apocalypse World didn’t have a list of “Basic Moves,” I would argue that players and GM should always assume there is a Basic Move called “Stuff the Average Person Can Attempt to Do.” This is a quick and easy fix to being overly mechanically minded and it is something I will keep in mind as I design the Heroes of Karameikos skill system (if it has one).

Is a Mechanics Based Mentality a “Bad Thing?”

Okay, that was a lot of verbiage that might come across as arguing that having a mechanics based mentality is a bad thing. It isn’t, at least not always. To cede some ground to the critics of 4e I mentioned earlier, a mechanics based mentality may actually be one of the ways role playing games evolved from wargames into games where actual role playing happened. To return to Over the Edge (2nd Edition), and the words of RPG game designer extraordinaire Robin D. Laws, “Role-playing games changed forever the first time a player said, ‘I know it’s the best strategy, but my character wouldn’t do that.’”

While Laws goes on to discuss, in high Greg Staffordian fashion, that this was how role playing games became an art form, I’ll go on to add that this is also the foundation for a kind of mechanics based mentality. Change the word “wouldn’t” to “can’t” (due to a lack of a specific skill) and you’ve got it down. The same logic that inspires role playing, also inspires a particular kind of “roll playing” and that’s great because it transforms “roll playing” into role playing. A mechanics based mindset might be limiting when the game being played wasn’t designed with that mindset in mind, but it is ideal when playing a game that was designed for that mentality. Some editions of Champions and every edition of GURPS are exactly such games. They contain highly curated skill lists and make explicit which skills can and cannot be used unskilled. Both are excellent role playing games that facilitate the creation of art as much as any other games one the market.

However, bringing a mechanics based mentality to every game you play is a mistake. The games underlying assumptions must match those of that mentality or it’s a mismatch. So too is the opposite mentality of “anyone can try” when applied to GURPS or Champions.

What I think is interesting about many modern story games, as opposed to Over the Edge and first gen story games, is that they often suggest an underlying mechanics based mentality. This can lead to player confusion as the “free form” play advertised clashes with the mechanics.

Who’s to Blame for Mechanics Based Mentality Related Player Confusion in Games?

This doesn’t mean that I blame modern story games for the creation of player confusion related to a mechanics based mentality, though it is ironic that games meant to expand player agency and story telling sometimes suffer from it. Instead, I blame Dungeons & Dragons, the first published role playing game for this problem. In particular, I blame the creation of the Thief class and how Gary Gygax adapted that class from its original design.

According to the interview I did with J Daniel Nielsen for my old podcast, when D. Daniel Wagner created the Thief class for the gaming group at Aero Games any character could attempt the things a thief could do. The difference was that the Thief had a number of uses per day that it would be successful at the task automatically. Thief abilities worked like Magic User spells. Gary changed this by making Thief skills something that was percentage based. Thieves could climb walls, detect traps, pick pockets, etc. and that left players wondering whether others could do these things to. If Thieves can climb walls at a certain percent, what about other people? You can see the kinds of confusion this causes in discussions of who can detect what kinds of traps in Moldvay Basic D&D. Only Thieves can detect traps, but everyone can detect traps on a 1 in 6 rolls (Dwarves on a 2 in 6 roll). Such contradictions lead to interpretations that differentiate between “room” traps and “treasure” traps.

None of which answers whether anyone other than Thieves can climb walls, but that was “solved” by the addition of “non-weapon proficiencies” and so begins the process of mechanical based thinking and some serious confusion for players. Seriously. Google “Moldvay Basic Traps” and you will find blog after blog and chat board after chat board discussing the topic. There is a general consensus, that there is a difference between room and treasure traps, but there is also confusion.

Gygax’s adaptation of the Thief class and Moldvay’s confusing rules regarding traps are only the beginning of D&D’s wanderings into mechanics based mentality. Original D&D had some of it around the edges, but

made a statement recently on his excellent newsletter . In Newsletter #37, he had an aside on his recent foray into playing older versions of D&D in preparation for his work on the Stranger Things and Dungeons & Dragons miniseries. The article (linked in the window below) made a key observation regarding the style of play reinforced in earlier editions of D&D, in particular he states that “Almost all old school dungeon delving is an off the cuff Player VS DM negotiation made in the moment.”While I might quibble a little around the edges regarding his specific examples, I think he has a point. Early D&D had some proto-mechanics based mentality rulings, but it was still supposed to be a game of negotiation and discussion and not of “looking at the character sheet to see if you have the right ability at this moment.” That changed with the release of 3rd edition Dungeons & Dragons. With that edition, Peter Adkison advocated for a new concept of table top rules design. He wanted games to use “templating” as their foundation, a foundation that would make computer translations easier and would “decrease contradictions.” In a sense, this system argues in favor of having the system do more, and the DM do less, work.

Peter articulated his reasons for preferring this mechanics based approach in detail in 30 Years of Adventure: A Celebration of Dungeons & Dragons.

The third school of thought said that complexity was okay as long as it made sense. What we really needed to do was create a system that was more modular and supported more styles of play. Jonathan Tweet once said, “D&D is the game that dares to define everything.” From stats on unicorns to listings of hundreds of monsters and spells to mass combat to charts on how to randomly generate dungeons, cities or nations, one thing that had been consistent throughout the history of D&D was its daring attempt to reduce everything to numbers, charts, and rules. But many of the rules in AD&D and 2nd Edition AD&D were inconsistent in application and needlessly limiting. Like the previous camp, this school of though argued that after twenty-five years D&D was due for a major overhaul but that the changes to the game should make the game rules more consistent, elegant, and support more possibility for different styles of play…

Yeah, I admit it. I was solidly in the third camp from the very beginning. D&D has always been complicated, and that never stopped it from becoming popular. Complexity wasn’t the issue — the problem was that too many rules just didn’t make good sense.

— Peter Adkison 2004 in 30 Years of Adventure: A Celebration of Dungeons & Dragons

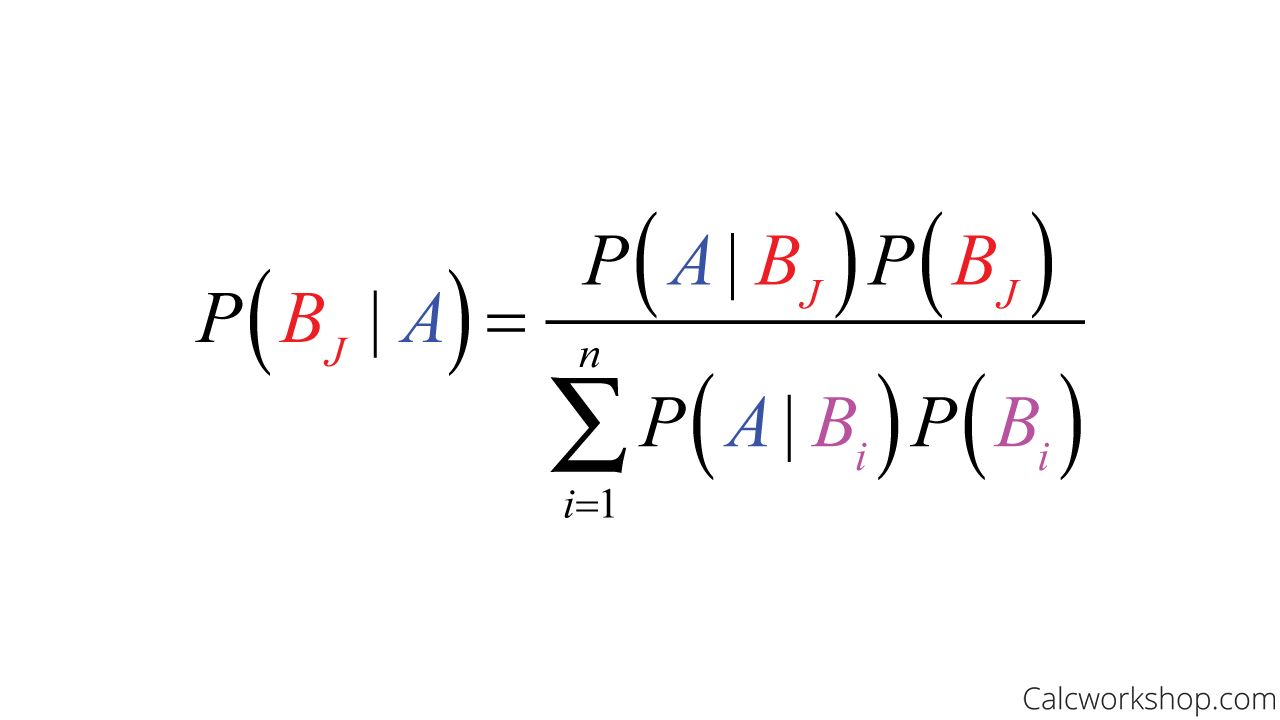

Note that his focus is on making the rules more consistent and to quantify almost everything. This is a pure mechanics based mentality and it’s why you can play an entire campaign of 3rd Edition D&D as a bartender running a tavern entirely as a solo player endeavor. You can roll dice to determine your every day earnings at your tavern and how many experience points you get for being a good Tavern Manager. You can also roll dice to haggle with the people you are buying goods from and roll to see how long it takes the cooper to build that 5GP barrel you need for the 30 gallons of mead you plan on purchasing. At no point in 3.x do you actually need a DM. The game is a Bayesian’s dream. You have your priors and you can run simulations all day. Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition, follows in the footsteps of GURPS, as an ideal game to run simulations with.

That doesn’t mean it isn’t ALSO a good role playing game. It is, and the ten year campaign I ran using the system is a testimony to how much I loved it. Love it as much as I do, it is still a very mechanics mentality based game. Right down to its inclusion of “trained only” skills. It’s no wonder players who spent so much time playing this game had difficulty transitioning to a reduced skill set and abstract “skill challenges” in 4th edition. They assumed that the skill challenges worked like the simulations in 3e, instead of as abstract narrative based events. That, and the fact that 4e formatted itself to appeal to Magic and MMORPG gamers, doomed it to criticism forever.

What is the Skill System Philosophy of Heroes of Karameikos?

I have a feeling that my system will be more in line with some of the games Monte Cook has designed since his work on 3rd edition D&D. While his work on D&D, and Champions earlier, was very mechanics oriented, his own personal DMing style and later game designs are very different. He loves “sure you can try that” assumptions and his most recent Cypher System games are very broad. As he describes his current mentality.

There were a number of excellent role playing games released in recent years that take as one of their design principles the idea that the rules should be tight and seamless. By that, I mean that the rules should provide clear procedures for everything that happens. Every contingency is covered in the text (or rather, the text is written so that if it's not covered there, it doesn't work.) If a character uses a frost ray, only a fire wall will stop it. Other situations do not matter. It's written like a board game. Just like how no one tries to reason that the race car in a Monopoly set should go faster around the board than the iron, there's no room for reasoning within the confines of the rpg, either. It leads to clarity, fewer rules arguments, and provides a valiant attempt at wiping out what had been a scourge of the game table for decades, the rules lawyer.

I, however, will not be designing any such games.

He has lived up to this statement. Cypher system characters are defined by statements that describe them, more than actual statistics. They are abstract. It’s an interesting system and one that has influenced the way I think about games in general.

But I don’t want to design a Cypher system style game for Heroes of Karameikos. I want it, and the publishable Fantasy Heartbreaker I spin off from my design work, to be a mix of the old and the new. I want to return to the old system of negotiation and danger, but I also want some more mechanics based elements. I just want to be clear on what the boundaries are. I want to have a game that focuses on interaction rather than simulation, but that has sufficient simulation to minimize arguments or feelings that your character’s survival and success depend on DM fiat.

In the post Hero/GURPS D&D era where skills are all articulated, if the player doesn't have a skill then that character is up Illithid Creek without a helmet.

When I think about some of the most fun I’ve ever had gaming I think about the D&D Encounters group I played with every week during the 4e run. I ran encounters for over 4 years, and I noticed a significant change in how the game played when Encounters shifted from the whole catalog of 4e books to the "Essentials and Newest Book" only stance.

The game ran smoother. There was less analysis paralysis. The players role played more. The players thought of their characters in terms of personality more than as a list of powers. The Essentials line of 4e books were when 4e found the right balance between mechanics based mentality and story facilitation. The addition of themes helped this, but so did the return to more archetypical character design and the clear articulation of the powers associated with a given thematic build. The fighter and cleric builds in the first Essentials book were game changing. Character builds in Essentials products were more "thematically" oriented than the calculated and Hero System-esque min/max affairs I had seen in earlier 4e designs.

It was a nice change, and it got me thinking how the addition of Feats and a scaling skill system made D&D less creative. That addition started with 3e, but the “you always only have a 50% chance of success” bounded probability really limited 4e.

In early D&D, if a character wanted to be a blacksmith, all the player had to say was that their character was a blacksmith. If a player wanted a character to be a blacksmith, poet, wizard, tumbling acrobat, scientist, engineer, the DM might have told the player that was ridiculous...OR the DM might have said "sure, why not" it doesn't affect the mechanics of the game and might make for interesting stories. In the post Hero/Gurps D&D era where skills are all articulated, if the player doesn't have a skill then that character is up Illithid Creek without a helmet.

I'd like to design Heroes of Karameikos as a return to an era where there is no scaling skill system and where characters can be good at a lot of things that are associated with their character's "core strengths" without needing to allocate skill points each level or without the ridiculous results of the 4e skill system where a 10th level character might have a higher DC to kick down the same door as a 1st level character.

If anything can be learned about how to implement a robust skill system -- inspired by the 3.x and 4e skill systems -- I think that the Dragon*Age role playing game and Robert Schwalb’s Shadow of the Demon Lord should be looked at for guidance. The DCs for difficulty in Dragon*Age are fixed early. They are a fixed point in space. Difficult is difficult. Challenging is Challenging. An average task in that game can be achieved on an 11 or better on 3d6 -- an exactly average roll. To that roll an ability bonus (+1 for average ability or +4 for amazing) and a "focus" bonus (if the character possesses a relevant focus) of +2 are added. An average person, with a focus in a relevant area, would add +3 to the roll making the chance of success 8+ on 3d6 on an average difficulty task. Rolling an 8+ on 3d6 is fairly easy -- with an 83% chance of success. Shadow of the Demon Lord is a little different. It still has fixed difficulties, but it doesn’t have skills at all. Instead, characters have professions and that profession lets them do things that the average person cannot. What things? That’s up to the player and DM to decide. Yeah, there’s a little Over the Edge DNA in Shadow of the Demon Lord, but there’s more 4e DNA, but don’t tell too many people that secret. It’s deep lore like the real nature of the Demon Lord.

What will Heroes of Karameikos Skill System look like?

I believe that there's no need to create challenges that are impossible for 1st level characters, at least not if you want free-wheeling games where low level characters take huge risks. Since I want to combine Old School negotiation and challenge with New School stability and story telling, I would prefer to make near impossible challenges merely supremely difficult. All one needs to do distinguish between the hard and the impossible is to use Man on Fire/Equalizer logic. In the Denzelverse, the main difference is between someone being competent at a task and being unlikely to succeed is whether they are "trained" or "not trained."

I propose sticking closer to Moldvay’s recommended “what to do when there is no rule for something a player is attempting to do” rule. He recommended using attribute rolls for almost any unforeseen challenge. His solution was similar to the one in the Perrin conventions, but it used a d20 instead of percentile dice. It’s a system that throws character levels out of the non-combat skill system, and I like that. It’s the same one Schwalb uses in Demon Lord too. I’d probably make an exception and add some "focuses" that match a character concept as the character increases in level. For example, the Rogue class in 5e has certain skills where it gets a double proficiency bonus. I might change this to advantage, but I like the basic concept.

Let's just have a look at how the skill system in D&D has evolved to get a look at where I might want to go to mix the D&D legacy rules with what I think is a wonderfully innovative Dragon*Age skill system. At some point I might even explore using Robin Laws' Gumshoe system for mysteries, but that is an entirely different discussion.

In the White Box of D&D there are no skills. Period. There are abilities and they affect very little about game play except the rate which a character advances in level. Eventually, with the addition of the Blackmoor and Greyhawk supplements, the ability scores have more mechanical effects, but there is still no skill system per se.

In Moldvay/Cook -- pre-Gazetteer/Compendium era -- edition of the rules added the "There's Always a Chance" rule on page B60 where you roll a d20 and compare it to a statistic (adding a -4 to +4 modifier to the roll based on difficulty) to account for all of the things a character could do outside of those abilities specifically granted by the character's class. This is the root for what became the eventual early skill system of D&D. The D&D Gazetteers, starting with Aaron Allston's Grand Duchy of Karameikos, give characters a number of skills based on their level. Success is determined by rolling equal to or less than an attribute on d20 with some modification for difficulty. Players can spend an entire skill choice to gain +1 to an attribute for the purpose of a skill check.

The AD&D "non-weapon proficiency" system introduced in Oriental Adventures and implemented in both the Wilderness Survival Guide and the Dungeoneer's Survival Guide is very similar to the Allston system, and pre-dates it. This system is very different from the earlier and broader AD&D "background skill" system in the Dungeon Masters Guide which gave characters background skills, but had no mechanical adjudication for those skills.

Until the 3rd edition, the Allston/Non-Weapon Proficiency system was the core skill system in D&D. It always seemed a little wonky to me. A character could use one choice to get a 55% chance to succeed at a skill (assuming an 11 stat), but had to spend an entire extra choice to get an additional 5%. That never seemed quite right. Additionally the difficulty of a task was entirely controlled by a character's full stat, rather than by the bonus, so an 18 in a stat meant a 90% chance of success for most tasks -- minus any modifiers. It just seemed to make good characters too good.

The 3rd edition of the game learned from the 90% is too good example and tied skill checks to the stat bonuses. These bonuses were designed to reflect the natural standard deviations of the attributes on a 3d6 curve and each equated with a 5% bonus against the challenge difficulty. A character with an 18 stat added +3 to a roll of a d20 and compared it to a difficulty. This skill system was very similar to that of earlier skill systems implemented in a number of prior systems. It worked, but 3rd edition had scaling difficulties. The inclusion of opposed rolls and the fact that characters got more skill points every level made it so characters had to make sure that they continued to spend precious skill points in ways that continued to be useful. Finding a difficult clue at 10th level had a higher DC than finding a difficult clue at 1st level because the DM would likely assume that the kinds of clues and traps a 10th level character is facing are different than those a low level character faces. Having DCs that ranged to extremely high numbers makes sense when characters get more skill points every level, but it can create some interesting externalities. Higher skill bonuses suggest the need for higher skill challenge values to maintain suspense which requires the higher skill bonuses, a kind of skill system moebius strip a never ending cycle of increase.

4th edition partly solved for the ever spending of skill points by having a system of "trained" and "not trained," but then muddied the mix with scaling DCs as the characters went up in level that was tied to ever increasing stats and magical bonuses. Ironically, the 4e system is actually flat. The increases are an illusion. Yes a 10th level character can beat up a 1st level character, but a 10th level character has as hard a time solving a 10th level problem as a 1st level character has of solving a 1st level problem. Amusingly, sometimes these problems might be the exact same thing.

I've always thought that the combination of scaling difficulties, increasing skill points to demonstrate improvement toward scaling difficulties, and a system of granularly listed skills detracts from rather than adds to fun in play. In the early days of Mutants and Masterminds, Steve Kenson spent many a day on the forums trying to convince people that Batman would just have Super-Dex and Super-Intelligence along with "training" in those skills that are "trained only." This would mean that he was good at all the skills, and that he didn't need to spend individual skill points. A lot of players disagreed. They wanted Batman to have tons of skill points and no “Super” attributes, even if the “special effect” of that super-ness was training.

The players who favored granular itemization of skills won out, and the M&M point buy system has never really recovered its balance since. I still think that skills are that games biggest weakness. Thankfully it has guidelines based on power level for power effects so the fact that skill points and powers don't really matchup mechanically point for point doesn't matter too much, but it still affects that game and makes that game feel less "superheroic" and more GURPS-ish. It becomes less narrative and more simulation.

I personally prefer games where characters can have skills that are independent of the level of the character. In Call of Cthulhu there are no character levels, just skill improvements through the use of skills. In D&D there are character levels, and I want to keep level based advancement in my design, but I'd love to see levels separated from skill use. There are tons of people who would be level 0 who would have tremendous skill at some science or artistic skill. There is no need to create nerfed NPC classes as 3rd edition did, or to create bizarre DC scaling tied to level as 4th edition did. All that matters is "trained" and "untrained" with a possible "how well trained" and "do you practice" added for good measure.

I’m leaning towards having Heroes of Karameikos adopt a skill system with fixed DCs, like Dragon*Age. This allows characters to take whatever “knowledge, artist, artisan, profession” skills they want limited only by how many skill choices their class allows. I might also have a class gave some small bonus. For example, a thief might automatically provide training in climbing and there might be a slowly scaling bonus (say +1 to +4 at level 20) against that fixed DC or a level at which they can choose to get advantage in a thief related skill. There is no need to have a large section of the rule book filled with skills and their descriptions and submechanics. Look at Dragon*Age, there is no set of three subskills for any of the focuses, unlike 4e's Acrobatics or 3e's Tumble. There is no need. If you are trained, you’ve got it. In Heroes of Karameikos, a fighter might pick your pocket and he might be trained in it too. He just might lack the additional “expert” bonus of advantage that only classes can get.

I don’t know. I’m still thinking about it.

I want to keep it simple. I don’t want my game to continue the trend of becoming more granular and complex. Sure, some players want D&D to have Advanced Squad Leader and GURPS levels of detail and granularity, but most want to sit around a table and have a good time. I’d like to find some compromise between the non-weapon proficiency system and the 3.x/GURPS system.

What do you recommend?

I will likely do a “fan” version of the rules using the Mystara setting and a professional version that uses my own Clockwork and Blackpowder Fantasy Setting

Feel free to steal what ever you like from my system - as detailed in my subsack as I post it.

Im checking out yours

Interesting thoughts. I like the name, "Mechanics Based Mentality". Our group hasn't called it such, but we have had debates about the merits of a skill system vs not.

I think my favorite method of blending these is backgrounds as 13th Age defines them. There are plenty of other systems that use similar ideas.

Your thoughts on 4e providing more RP opportunities is opposite of mine. The "powers" that everyone had rules the table. No one thought to do anything outside what was listed on the sheet, and that took time. As the number of powers increased with level, the Tyranny of Choice took over, and people began to take too long to find that one perfect power for the current situation.