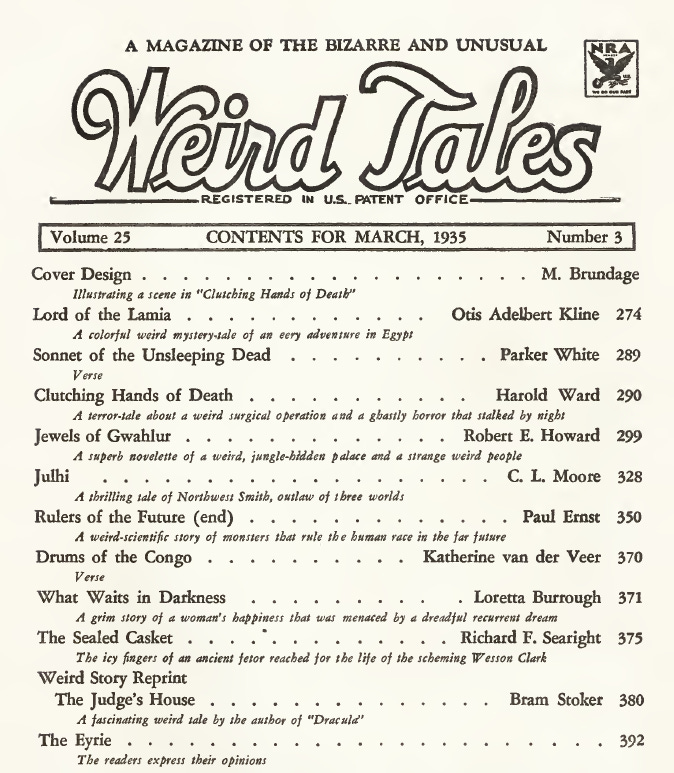

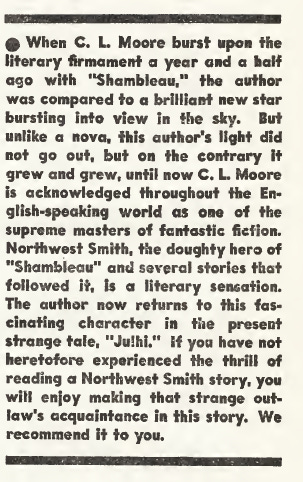

The March 1935 issue of Weird Tales featured Julhi, the fifth of Catherine Lucille Moore's Northwest Smith tales. That same issue also featured Robert E. Howard's Jewels of Gwahlur, a classic Conan tale.

After a year of writing Northwest Smith tales, Moore's Julhi manages to integrate what are now the "old stand-by's" of the Smith series with an energy that keeps the repeating narrative devices feeling fresh -- and to be fair, some of what is going on in this tale is quite fresh. Like in the first Northwest Smith tale, Moore gives us a brief introductory paragraph reminiscent of a campfire story. It's a device that Moore had abandoned in the prior three stories, but it helps to set the tone here and notify the audience that we are going to be reading an event that transpired in Smith's past.

The tale of Smith's scars would make a saga. From head to foot his brown and sunburnt hide was scored with the marks of battle...But one or two scars he carried would have baffled the most discerning eye. That curious, convoluted red circlet, for instance, like some bloody rose on the left side of his chest just where the beating of is heart stirred the sun-darkened flesh..."

The "campfire" paragraph provides Moore with a couple of advantages, and one major challenge, as the story unfolds. First and foremost, this preamble let's us know a little bit about the story we are about to read, we will be learning just how Smith acquired that "bloody rose" scar. Fans of Smith will be getting a glimpse into his, as yet, largely unrevealed past. Second, our curiosity as readers is piqued as we wonder just what kind of beast or device would leave such a wound. As mentioned earlier though, these advantages don't come without a price. By revealing to the audience that the story takes place at some point in Smith's past, any fear that Smith will fail to overcome the challenges within the tale can be easily cast aside. We know he survives because we know he bears the scar.

It's harder to create an aura of mystery and weird terror when the audience knows the outcome, but Moore knows what she is doing. She immediately disorients the reader, by inserting them in medias res -- along with Smith -- into an unknown environment. As the story begins we find Smith literally in the dark without "the faintest idea of where he was or how he had come there.1" Adding to his mysterious surroundings, Smith is immediately attacked by some unknown and unseen foe and falls unconscious. The reader may know that Smith will find a way out of the situation, but the reader also feels the urgency of the situation in which Smith has found himself.

As a side note, as in other Moore tales, much could be made in this story about the use of light and dark and how she uses them to create discomfort for the reader. Much of this story takes place in the dark and the majority of the references to light are referring to one character's ability to open a portal between worlds.

When Smith awakens from his unconscious state, he finds once more that he is not alone. Moore's descriptions of movement are identical to the ones she used to describe the unseen assailant, maintaining the uncomfortable anxieties she created earlier as long as possible. This time, Smith takes action and finds -- much to his pleasure -- that it is now a fellow prisoner and not an unknown horror who has joined him in this mysterious place. Smith's new companion, the fair Apri, knows where Smith is and why he is here and quickly shares what information she has with Smith and the audience.

Here Moore exhibits one of the least appreciated skills in writing. She deftly provides the audience with much needed exposition in the form of natural dialog. When Apri is discussing the "haunters of Vonng," who are the slaves of "Julhi," it is conversational rather than expository, yet it fills in all of the necessary information to inform the audience how dire the circumstances are and how mysterious the place Smith has found himself in is. One of the ways Moore accomplishes this is to have Smith's thoughts interact with Apri's dialog to fill in the blanks.

What will come?” he demanded. "What is the danger?”

"The haunters of Vonng,” she whispered fearfully. "It is to feed them that

Julhi’s slaves bring men here. And those among us who are disobedient must feed the haunters too. I have suffered her displeasure—and I must die.”

"The haunters—what are they? Something with a touch like a live wire had me awhile ago, but it let me loose again. Could that have been”

"Yes, one of them. My coming must have disturbed it. But as to what they are, I don’t know. They come in the darkness. They are of Julhi’s race, I think, but not flesh and blood, like her. I—I can’t explain.”

For example, when Apri mentions that Smith is in Vonng the reader is immediately granted access to Smith's thoughts, rather than having to read Apri explain what and where Vonng is. And it is a place reminiscent of sunken R'lyeh:

The stone had been quarried with unnamable [sic] rites, and the buildings were queerly shaped, for mysterious purposes. Some of its lines ran counter-wise to the understanding even of the men who laid them out, and at intervals in the streets, following patterns certainly not of their own world, medallions had bedn set, for reasons known to none...

Like many of the locations in H.P. Lovecraft's fiction, Vonng is a city that exists at a nexus of worlds, where the geometry of the universes allow one universe to affect others if they have the proper means of communication. We quickly find out that Apri is a vessel through which Julhi, a horrifying being from another world, can bring people into her own "Vonng" to serve as food.

As mentioned earlier, Moore is using many of the narrative elements from prior Smith stories in this piece. In Scarlet Dream, Smith found himself transported to another universe. In Black Thirst, Smith found himself in a vast and unending castle/city whose ruler could manipulate the geography to make it a prison. In all the prior tales, save Dust of the Gods, the villain was some form of vampiric inspiration for a creature of classical myth. Shambleau was the vampiric origin of the Gorgon, the Alendar was the elemental horror version of Dracula, and the very planet in Scarlet Dream was a blood feeding terror. In Julhi, the eponymous villain seems to be the vampiric inspiration for the Siren or Lorelei.

Like most of Moore's vampires, Julhi feeds on something other than blood and in this case it’s something in addition to blood. The Alendar fed on beauty, Shambleau fed on sexual pleasure and desire, and Julhi feeds on emotion:

but to experience the emotions we crave we must have physical contact, a temporary physical union through the drinking of blood.

Julhi is a traditional vampire, in that she drinks blood, but a non-traditional one in that she feeds on the experiences, sensations, and emotions of the victim.2 Julhi feeds on all kinds of emotion, save possibly one that is the key to the tale.

Of all of Moore's creatures, the Julhi is the most interesting to date and quite unique. I was taken aback by Moore's description of the creature and how she managed to bring horrifying imagery to my mind while describing the creature as one of beauty:

He caught his breath at the sleek and shining loveliness of her, lying on her black couch and facing him with a level, unwinking stare. Then he realized her unhumanity, and a tiny prickling ran down his back -- for she was one of that very ancient race of one-eyed beings about which whispers persist so unescapably in folklore and legend, though history has forgotten them for ages. One-eyed. A clear eye, uncolored, centered in the midst of a fair, broad forehead. Her features arranged in a diamond-shaped pattern instead of humanity's triangle, for the slanting nostrils of her low-bridged nose were set so far apart that they might have been separate features, tilting and exquisitely modeled. Her mouth was perhaps the queerest feature of her strange yet lovely face. It was perfectly heartshaped, in an exaggerated cupid's-bow, but it was not a human mouth. It did not close, ever. It was a beautifully arched orifice, the red lip that rimmed it compellingly crimson, but fixed and moveless in an unhinged jaw. Behind the bowed opening he could see the red, fluted tissue of flesh within.

Sexual imagery aside, this description is highly disconcerting. When added to the slightly serpentine arms, indescribable lower half, and feather crest above the head, we have a truly haunting creature. In fact, the imagery in my mind was a kind of combination of the monster from The Man Trap, a serpent (diamond shaped head and all), a lamprey, and a peacock. Not something I would want to meet while trapped in an alternate dimension. It's also a creature I would love to see illustrated.

Though Julhi cannot speak she can, like the Lorelei or Sirens of myth, sing, and her song creates a hypnotic state that manipulates the emotions of the listener. Smith is run through the gamut of emotions and the ride only stops on two occasions. Once, it is stopped because Julhi has experienced more powerful experiences than she has ever experienced before. The other time Julhi withdraws, without comment I might add, is when Smith remembers his first (and likely only) true love. This love is one that hints at horrible loss in this tale. Smith’s memories of this true love is a place where it seems Julhi will not go, and is evidence of another recurring theme in Moore's tales. She often places love in a favored, though typically tragic, position over sexuality. Sexuality and sexual desires are more base than the love she often presents, as was evidenced in the earlier discussion of beauty in Black Thirst.

While Julhi herself may be (mythically within the Smith-verse where the cultures of Venus and Mars are in our ancient past) the inspiration for the Siren or Lorelei, she is not representative of her eerily beautiful race. As the story unfolds, we learn that she is an aberration among her people, a corruption if you will. This makes her markedly different from Shambleau and the Alendar who were representative of their respective species. Here Moore might be commenting on humanity itself and how those who live vicariously through others, and to the destruction of those others, are a kind of leech to be shunned by society.

One thing is certain, when Moore is writing she is doing more than telling tales. She’s making some kind of commentary on human nature.

Previous Encountering Northwest Smith Entries:

Imagine opening a role playing game session with your players’ characters in the pitch black, only to have the bare minimum of sensory input. The video game Darkest Dungeon and the Shadowdark role playing game emphasize the importance and danger of abject darkness. How could you use this in your own games?

The feeding on memories and experiences reminded me of the Level Drain powers of undead in older versions of D&D. While it can be hard for a DM to create a sense of fear for his or her players, Level Drains and the consequences of losing all character levels provided a nice proxy for the fear of a horror story.

I love C.L Moore and welcome anything related. Great post!